Fertile Grounds: How Seabird "Waste" Benefits Land and Sea

“You work on seabird colonies? How can you stand the smell?” That's a common reaction when I mention my work as a field biologist. While it's true that guano can be pungent, it's also a key source of nutrients — and the more researchers tease out seabirds' contributions to both islands and oceans, the more apparent it's become that thriving colonies (and their poop) play key roles in a healthy environment.

Seabirds make their living foraging across huge areas of ocean, often far from the islands where they roost and raise their young. For example, Sooty Shearwaters raising young on islands south of New Zealand venture up to 1,200 miles roundtrip to Antarctic waters to bring meals back to their growing chicks. At bustling colonies, food is then digested and waste is excreted as a white-washed bounty of nutrient-rich guano.

“Bird-derived nutrients in the form of guano have long underwritten human agriculture,” says Sea McKeon, ABC's Marine Program Director. “We've been using these relationships between birds and the ocean, and birds and their nesting habitat, for centuries.”

Before factory-made synthetic fertilizers became widely available in the early 1900s, farmers were desperate for highly potent guano to boost crop yields. Ships from the U.S., Germany, Spain, and the British Isles, for example, traveled thousands of miles to the seabird colonies and rich guano beds of Peru's Chincha Islands to load up on the valuable fertilizer, a prized commodity harvested there since pre-Incan times. Nations rattled sabers over guano and claimed islands that supported seabird colonies as territory to gain access to the “white gold.”

The Straight Poop on Guano

Today, we know that this rich resource, left where it's dropped, yields great natural benefits. Guano is rich in nitrogen and phosphorus, two elements that help feed the base of the food chain. But these same nutrients get a bad rap when it comes to coral reefs, because reefs can suffer when human-generated sewage and fertilizer runoff high in these same elements trigger smothering algae blooms. Since seabirds and coral reefs have coexisted for millions of years, does guano have a different impact on the reefs — and possibly a beneficial one?

As a University of California, Santa Cruz (UCSC) graduate student, Susanna Honig wanted to find out. “It was a question that my graduate advisors Donald Croll and Bernie Tershy had long been thinking about,” she says. But first she had to figure out whether the guano is even present in the reef system. “There was a prevailing idea that maybe the nutrients were being flushed out by wind and wave action, and we wanted to challenge that,” she says.

Working in Kailua and Kaneohe Bay on O‘ahu, on Hawai‘i's windward side, Honig and her colleague Brenna Mahoney collected water and algal samples adjacent to the small offshore islands that support Wedge-tailed Shearwater and other seabird colonies. On islands with more nesting seabirds, they found both higher levels of phosphorus in surrounding waters and more seabird-derived nitrogen in nearshore algae.

“So that was one part of the puzzle,” says Honig, who now heads UCSC's Academic Excellence Program. “The nutrients weren't being washed out of the system but were instead sticking around and being taken up by algae.” Unlike algal blooms caused by human activities, these guano-enriched algae in turn can better support herbivorous “grazing” fish that keep the algal growth in check.

“If seabird guano is associated with a healthy herbivorous reef fish population, that's different from the impacts we're seeing from human sewage, fertilizer, and overfishing that reduces populations of algal grazers. It's really different from the simple story of ‘nutrients are bad for coral reefs,'” says Honig.

As Honig explains, human activities that add additional nutrients and remove fish from the ocean can muddle the picture of guano's positive impact on coral reefs — an impact that may only be obvious in settings such as untouched tropical ecosystems that are otherwise low in nutrients. So, what happens when you take the people out of the picture?

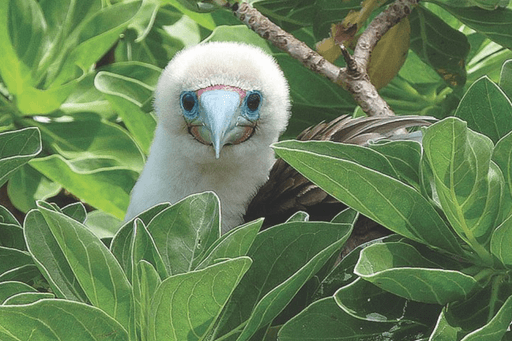

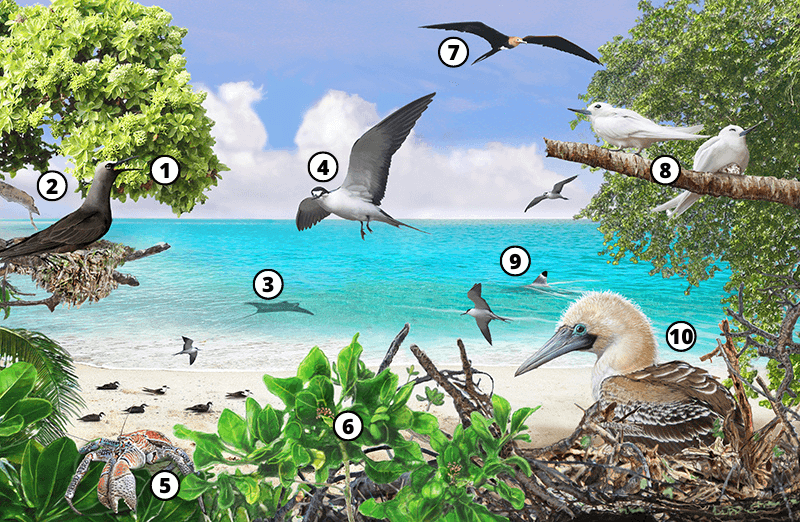

Forests and Fish

Palmyra Atoll sits just north of the equator and 1,000 miles south of Hawai‘i. There, tens of thousands of Red-footed Boobies, Great Frigatebirds, and Black Noddies occupy stick nests that speckle the hot, humid atoll's towering Pisonia and Beach Heliotrope trees. Below, Sooty Terns blanket the beach on their coral-scrape nests. This remote, seabird-rich cluster of nearly 50 low-lying islands is surrounded by a relatively undisturbed coral reef — and drenched by an annual average of 175 inches of rain. It offers scientists an ideal place to study the effects of guano in the absence of human impacts.

“Doug McCauley and Hillary Young of the University of California, Santa Barbara have been looking at that whole topic of seabird-derived nutrients and marine linkages at Palmyra since 2010, starting when they were graduate students,” says Alex Wegmann, lead scientist for The Nature Conservancy, which co-owns and manages Palmyra as a research site and wildlife refuge with the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service.

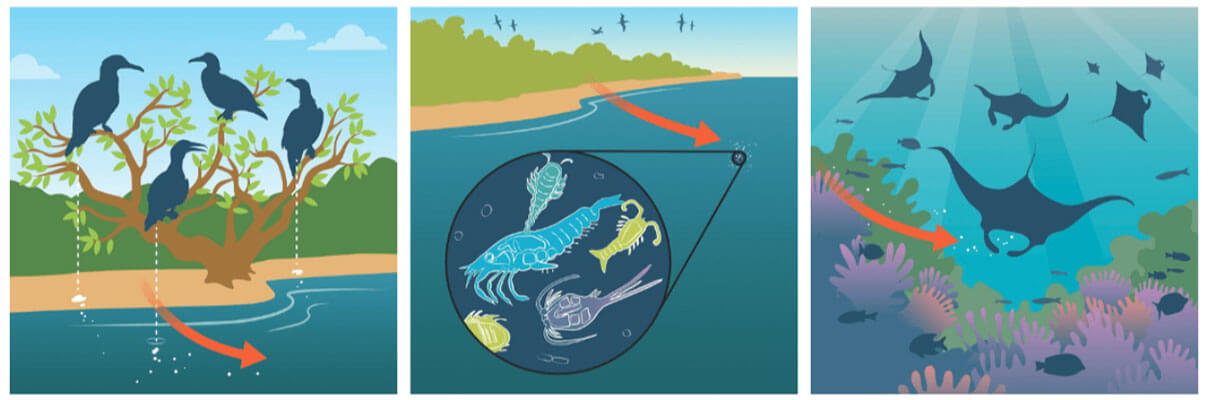

McCauley and Young were able to trace the seabird-generated nitrogen and phosphorus flushed from the atoll into surrounding waters. There, the guano nourished zooplankton blooms that attract manta rays and other plankton feeders. The researchers found more manta rays drawn to the native forest-dominated coastlines where the seabirds preferred to nest — which generated 25 times more nitrogen compounds compared to runoff from nearby areas of cultivated Coconut Palms.

Making what they called the “wing-to-wing” connection, from seabirds and native trees to manta rays and other animals in the nearshore ecosystem, McCauley and Young showed that because seabirds generally shun Palmyra's Coconut Palm groves as nesting sites, this type of land use seems to disrupt a natural and beneficial chain of interactions linking seabirds to offshore species.

“At Palmyra, the seabirds are such an integral part of the native forest,” says Wegmann. “Not only have researchers measured increased productivity in the marine environment, such as an increase in plankton thanks to seabird inputs; they have seen the same effect in the native forest ecosystem: greater biodiversity of land crabs, geckos, insects. Everything is amplified with that nutrient input.”

Work is now underway to remove approximately 2 million of Palmyra's coconut trees, which were planted centuries ago as part of a coconut-oil operation and now crowd out native trees. That project will give the fast-growing native forest a chance to recover and improve nesting habitat for the atoll's seabirds.

Wegmann sees the effort as a potential blueprint for other settings: “Palmyra's scenario as a coconut-dominated plantation is a prominent land use across the Pacific. We feel that these results coming out of Palmyra are applicable at a global scale when you're thinking of low-lying islands.”

Thinking beyond the reef and out to the deep waters surrounding Palmyra, Wegmann also reflects on the role seabirds play in the larger ecosystem: “They're a nutrient contributor on land and in the nearshore system, but they're also really important species out in the pelagic zone, where they're top-level predators. Seabirds are unique in their ability to stitch all these habitats together through their interactions.”

Rats and Resilience

Halfway around the world from Palmyra, the Chagos Islands form a small archipelago in the central Indian Ocean. This chain of islets offers a different type of living laboratory for studying the ways that seabird guano impacts the surrounding environment — and what happens when non-native predators interfere.

By preying on bird eggs and chicks, introduced rats drastically reduced or eliminated seabird populations on some Chagos islands, while others nearby that lacked the rodents teemed with boobies, terns, shearwaters, tropicbirds, and frigatebirds. In 2018, a research group headed by Nicholas Graham of the United Kingdom's Lancaster University reported that without rats, guano flowed freely into surrounding waters, where it nourished algae, sponges, and fish on adjacent coral reefs.

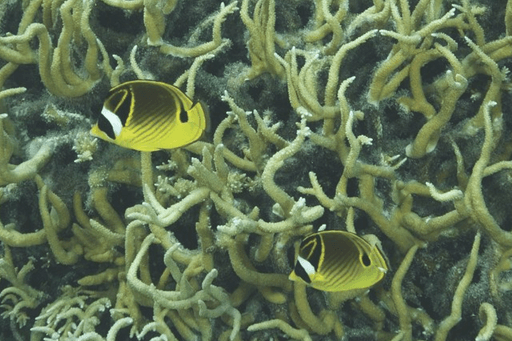

Overall, the biomass of fish was more than 50 percent higher near Chagos' rat-free islands. Corals also grew faster, and the types of coralline algae that support young coral were far more abundant. Subsequent work on the Chagos Islands has shown that seabirds' contributions may help reefs recover more quickly from coral bleaching events triggered by high water temperatures.

Research at remote, rat-free sites in New Caledonia and Fiji reported in the last several years shows similar results: Where seabirds are abundant, guano provides a significant source of nutrients, helping to nourish corals, including a dominant branching species named Acropora formosa.

Teaming Up With Seabirds

As more information emerges about the ways that seabirds enrich and stabilize ecosystems, ABC scientists are exploring the idea of both protecting the birds and harnessing their “guano power” through a system dubbed “bioshielding.” ABC's Sea McKeon wants to build on the cascade of ecological benefits that seabirds contribute, through projects that would pair seabird conservation with habitat restoration. The goal is to ramp up protection of small, storm-vulnerable islands throughout the Atlantic and Pacific.

McKeon explains: “We know that islands with mangrove systems, seagrass beds, and coral reefs survive hurricanes and cyclones much, much better than unprotected islands. What's been missing from the equation is what seabirds bring to those systems.” Boosting seabird numbers could increase this “shielding” effect by upping the nutrient inputs that enhance coastal vegetation and nearshore reefs.

Refuge managers are already getting help from seabirds to heal fragile seagrass beds in the Florida Keys that had been torn up by boat propellers, hulls, and anchors. By adding specially designed stakes where cormorants, pelicans, and other seabirds can roost and add nutrients to the water, these critical fish nurseries recover from damage more quickly than do unfertilized sites.

Saving Winged Benefactors

In 2018, biologists from the University of Santiago in Spain reported in Nature Communications that seabirds' contributions reverberate far beyond local ecosystems. “This research is showing that seabirds are significant contributors to the global nitrogen and phosphorus cycles,” explains Brad Keitt, ABC's Oceans and Islands Director. The study confirmed that as seabird guano breaks down into various forms of nitrogen and phosphorus, including airborne elements, it helps nourish a wide range of plants and animals both nearby and far from its original source.

“Not only is the amount of nutrients that they transmit between oceans and land significant,” says Keitt, “but even more so, the type of nitrogen and phosphorus excreted by the birds is more readily ‘bioavailable.' In other words, it's particularly designed to be taken up and used by those ecosystems.”

Ironically, as we come to better understand the critical roles seabirds and guano play in ocean systems, seabird populations are declining worldwide. Overall numbers have dropped 70 percent globally over the past 60 years, with more than a third of seabird species now facing extinction. Many experts believe the actual decline over the last several centuries has been closer to 90 to 99 percent.

Harnessing the power of seabirds and upping the benefits they provide to both land and sea may involve broadening seabird protection efforts beyond a focus on just those that are most threatened. “Often the species most associated with the research coming out on seabirds' role in ecosystems are not the world's rarest species,” says Alex Wegmann. These include widespread species such as boobies, terns, and frigatebirds. “They're the working class, the proletariat of the seabirds — from the bird conservation perspective they've been ignored, even though they are playing a major role in keeping these systems functioning. I do think there's a rising awareness of the importance of ecosystem function and the importance of seabirds in that role.”

Sea McKeon likens the challenge we now face in protecting seabirds to Samuel Taylor Coleridge's “Rime of the Ancient Mariner,” in which a sailor thoughtlessly kills an albatross, unleashing a wave of bad fortune, for which he must atone. “The modern thought about that poem is that an albatross around your neck is a problem of your own creation. But really, it could be interpreted that it's about an opportunity lost: You had the chance to do the right thing, and you didn't take advantage of it. I want to make sure we don't lose the chance to do something now.”

Our opportunity is there to slow or even reverse seabird declines — we have the tools, whether it's removing invasive predators and plants from islands, managing fisheries to protect seabirds and their prey, or creating “safe havens” where seabirds can nest, sheltered from the impacts of sea level rise. In doing so, we'll preserve not just the birds, but the contributions they make to keep ecosystems thriving. Think of it as the sweet smell of seabirds making the ocean a healthier, more productive place.

| Martha Brown is a writer, editor, and field biologist. She lives in Santa Cruz, California. |