Midway Between an Ark and a Hard Place

Steeped in history and a bird paradise beyond compare, Midway Atoll continues to face existential challenges that conservationists work hard to fix.

The corner of Peters and Morrell Streets is my favorite place in the world's largest albatross colony. There, at the edge of what was once the grassy Navy parade grounds, I can look out across a nearly solid carpet of tens of thousands of nesting albatrosses, backed by the aquamarine lagoon that stretches between Midway Atoll's three islands. This scene, on Sand Island, is in constant motion, packed with 3-foot-tall seabirds tidying their nests, swapping incubation duties, and squabbling with neighbors. Over the colony, black-and-white Laysan Albatrosses and chocolate-brown Black-footed Albatrosses ride the wind, soaring and dipping in seemingly effortless flight.

I've visited this corner many times since I first arrived at what was then the Midway Naval Air Station in 1988. As I've returned for various projects over the years — most recently to help lead the annual albatross nest count — I've witnessed Midway's remarkable makeover from a military installation that once housed 10,000 troops to a vibrant wildlife refuge, national memorial, and national marine monument, where more than 1 million albatrosses arrive each fall after months of oceanic feeding. And I've come to admire the driving force behind this transformation — a small but dedicated cadre of U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (FWS) biologists and refuge managers. With the help of monument partners, nonprofit groups, contractors, and volunteers, they're reversing a backlog of human impacts in their efforts to make Midway a truly safe haven for wildlife.

The author and her husband are dwarfed by the sheer size of a Laysan and Black-footed Albatross colony on Midway's Sand Island. Photo by Craig Thomas.

Tiny Islands, Out-sized History

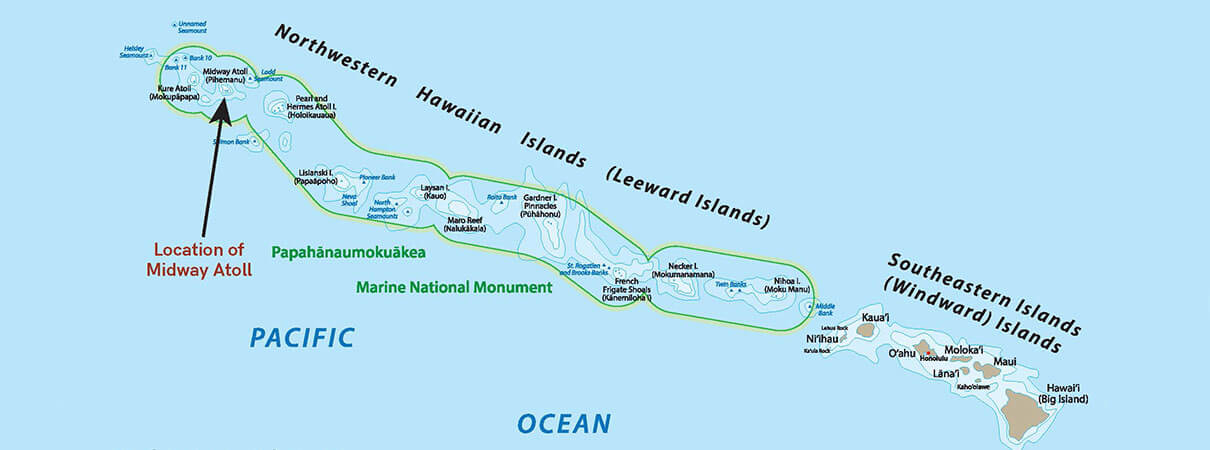

Best known for its role in World War II's most pivotal naval battles, Midway Atoll lies more than 1,300 miles from Oahu, near the terminus of the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands. The atoll's three islands — Sand, Eastern, and tiny Spit — cover about 1,500 acres.

Native Hawaiians dubbed Midway Pihemanu, “loud din of birds,” but apparently never established a settlement on the sandy atoll. The United States had claimed the far-flung islands as a potential source of prized, bird-produced fertilizer under the Guano Act in 1859, but apart from a handful of shipwrecked whalers who set up temporary shelters, it remained unoccupied by humans until the turn of the 20th century.

In 1900, after Japanese feather hunters were found slaughtering the islands' birds, President Theodore Roosevelt put Midway under Navy Department control, both to protect the birds and other wildlife and to establish a military presence at the strategic location, midway between the United States and Asia.

Then in 1903, the Commercial Pacific Cable Company arrived to set up operations that would boost the telegraph's signal across the Pacific to the Philippines. Thus, Midway became a link in the first around-the-world communications system.

Hawaiian Island Chain. Map by Rainier Lesniewski/Shutterstock.

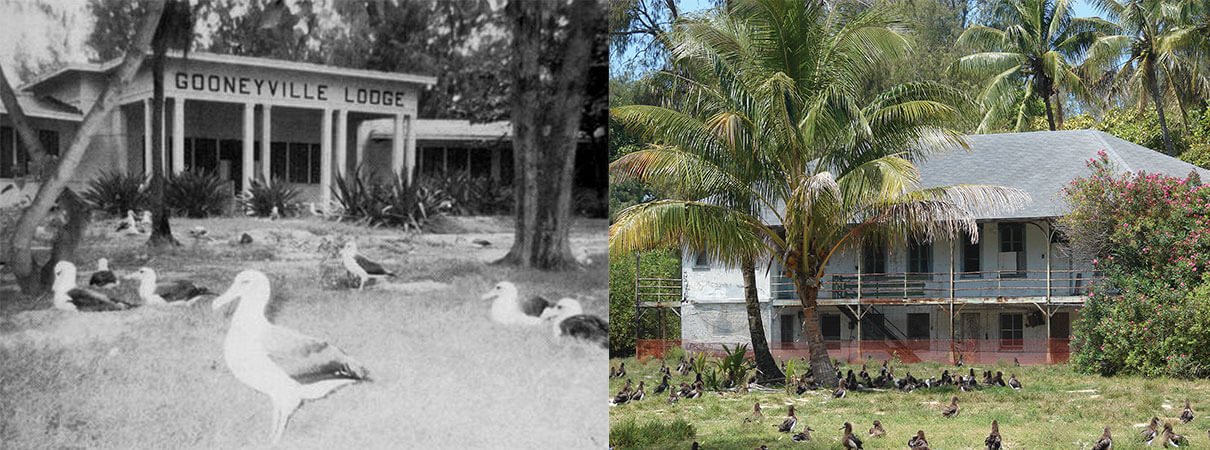

Pan American Airways also needed a stopover point for the first trans-Pacific commercial flights. Starting in 1936, the airline's Clipper “flying boats” landed on the atoll's lagoon to refuel on their way to Asia. White-liveried staff met the well-heeled passengers, who slept at the Gooneyville Lodge, complete with albatrosses nesting on the lawns. It was a short-lived enterprise. By 1941, the buildup to World War II displaced civilian use of Midway and transformed the atoll into the military base it would be for the next 50-plus years.

Military needs sometimes put wildlife in harm's way, but military properties can also be fertile ground for research and conservation. In the case of Midway, biologists had a unique chance to study the albatross population. Part of the impetus for research was to solve the problem of military planes colliding with birds mid-flight, but much more came to light as well: Over the years, biologists banded more than 250,000 albatrosses at Midway, work that revealed many details of the birds' life histories, including their long lifespans and year-to-year fidelity, both to their nest sites and their partners.

In 1956, as part of his work on the colony, FWS ornithologist — and later North American Breeding Bird Survey founder and field guide author — Chandler Robbins banded the albatross since dubbed Wisdom. Today, Wisdom is at least 68 years old, the world's oldest known-age wild bird. She still builds her nest behind the cement-block bachelor officers' quarters where she was first banded and where she has raised more than three dozen chicks — a remarkable contribution to her species.

By the 1980s, Midway's strategic importance waned, as improved remote monitoring systems and long-range aircraft and submarines came into operation. In 1993, the Navy initiated plans to shutter its facilities. A few years later, control of the area was transferred to the U.S. Department of the Interior (click below to learn more).

READ MORE: Midway Offers Refuge to More than Just Albatrosses

Development and invasive exotic species have compromised much of seabirds' former nesting grounds in places such as the main Hawaiian Islands, making efforts to protect far-flung atolls even more crucial. To better envision the importance of Midway to seabirds, let's take a quick armchair tour:

Although the albatrosses take center stage, Midway Atoll's three islands provide crucial habitat for many other seabirds. Black Noddies place their messy nests in Sand Island's ironwood trees, while larger Brown Noddies nest on the ground. Great Frigatebirds swipe nest material from neighboring Red-footed Boobies. Pairs of White Terns perform graceful aerial pas de deux, black-and-white Sooty Terns screech their “wide awake” calls 24/7, and Red-tailed Tropicbirds twitch long red tail feathers against the brilliant blue sky as they catch the midday breezes, “flying” backwards in their unique courting routine.

Deep nesting burrows riddle the sandy soil, harboring nocturnal Bonin Petrels and Wedge-tailed Shearwaters. Add Gray-backed Terns, Brown and Masked Boobies, and Christmas Shearwaters to the mix, and in all, more than 3 million seabirds rely on Midway for nesting habitat. And there's cautious optimism that more will join them: Over the past eight years, two pairs of Short-tailed Albatrosses — listed as Endangered under the U.S. Endangered Species Act — have successfully raised chicks, offering hope that this species, once numerous throughout the Pacific, will someday establish a colony on the atoll.

— Martha Brown

Cleaning House

Credit the Navy for a heroic cleanup effort. By the time Midway came under FWS management in 1996, more than $90 million had been spent to remove scores of unused buildings, miles of submarine net, and hundreds of above- and underground storage tanks. Crews also removed antennas and overhead wires that had killed thousands of birds.

Introduced species posed other challenges. Beginning when they arrived with the Navy in 1943, Black Rats preyed upon the atoll's birds for decades. They quickly wiped out Laysan Rails and Laysan Finches, birds that had been shipped over in the late 1800s from Laysan, 385 miles to the southeast, after that island had been stripped of vegetation by introduced rabbits. (The rail is now extinct, though the finches survive at Laysan.) Eggs and young of burrowing Bonin Petrels were also easy pickings — from a population of half a million before the rats' arrival, petrel numbers plummeted to fewer than 5,000 by the 1980s.

Seabird eggs and native plants such as the naupaka shown above were easy pickings for introduced rats, which have since been removed. Photos by Breck Taylor.

The omnivorous rats also decimated the atoll's plant life. Leafless remains of Beach Naupaka dotted the Eastern Island research plots where I worked in the 1980s, stark reminders of the rats' impact. The native shrub provides critical breeding habitat for shade-dependent birds, and with the leaves stripped away, tropicbird and shearwater chicks died in the direct sun.

In 1995, FWS biologists teamed with U.S. Department of Agriculture staff in a successful effort to rid the island of rats. Bonin Petrel numbers rebounded with a vengeance. Although the numbers are hard to pinpoint, as many as 1 million of the petrels now nest on the atoll, swarming over the breeding colony each evening after a day of feeding on fish and squid. Naupaka also flourishes now, plus plants I never saw when rats were present, such as the native Tribulus or Puncture Vine, which sprouted from remnant seeds. Ridding the island of rats also made it safe to bring Laysan Ducks to Midway's Sand and Eastern Islands from Laysan Island in 2004 and 2005. This complex and highly successful translocation effort created “insurance” populations of this Critically Endangered species.

Other nonnatives have proved more stubborn. Verbesina enceloides, called Verbesina or Golden Crownbeard, is a pretty plant with fuzzy green leaves and yellow daisy-like flowers. In the 1950s, Verbesina's wind-borne seeds escaped Sand Island's home gardens and spread across the atoll. Dense stands of the crownbeard choked out native plants, smothered nesting sites, and created habitat for mosquitoes that transmit avian diseases. I came to dread counting nests in head-high Verbesina thickets, where you could quickly lose your way and where we'd occasionally find an albatross struggling to free its wings from the tangled, unforgiving weeds.

Introduced Verbesina formed tall, dense stands that transformed once-open areas and choked out native plants. Photo by Forest and Kim Starr.

After nearly a decade of intensive control work by FWS staff, the war on Verbesina is nearly won. Supported by the National Fish and Wildlife Foundation, ABC, Defense Base Services, Inc., The Friends of Midway Atoll National Wildlife Refuge, and others, the effort transformed weed-choked fields into wide-open vistas, where restoration teams are replacing Verbesina with bunch grasses and other native plants.

“It's been extremely gratifying to witness the positive transformation of Midway's terrestrial habitat from expansive fields of Verbesina to one approaching a native paradise,” says John Klavitter, National Invasive Species Coordinator for the National Wildlife Refuge System, and the Midway refuge's former deputy manager.

New Trouble in Paradise

Working at Midway can be like playing an ecological game of Whack-a-Mole: As soon as one problem appears to be under control, another pops up.

While participating in the December 2015 nest count, I noticed several Laysan Albatrosses on adjacent nests, each with an identical bloody wound on the back of its neck. Over the next few days, we found more and more birds with similar injuries, some dying or already dead.

It took a motion-sensing camera trap to reveal the culprits: After dark, tiny gray House Mice were attacking the albatrosses, burrowing under their feathers and gnawing away at the birds' flesh as parents remained steadfast, incubating their eggs. Not having evolved with mammalian predators, the birds had no strategy to defend themselves. The mice injured 480 birds that year, killing at least 52 and triggering more than twice the normal number of birds to abandon their eggs.

Wisdom the Laysan Albatross, show in 2011 with one of her many offspring. At least 68 years old, she regularly returns to Midway to nest. Photo by John Klavitter/FWS.

The discovery took everyone by surprise. Mice had arrived on Navy ships decades ago and never caused the albatrosses any harm. For some reason — perhaps that year's El Niño-related drought or the absence of Verbesina seeds as a food source — the tiny rodents suddenly had become a threat.

For now, refuge biologists have been able to head off further damage by hand-baiting affected areas. They've also teamed up with experts from the nonprofit organization Island Conservation to plan for a more extensive effort to protect native species by eradicating mice from the atoll.

FWS biologist Beth Flint explains the reasoning behind this ambitious effort: “The potential harm to a substantial proportion of the world population of Laysan Albatrosses moved us to undertake the complex job of removing introduced mice at Midway. Ridding seabird colonies of mammals introduced by humans is the most direct and immediately rewarding conservation action we can take to protect oceanic islands.”

With an environmental assessment now complete, the project is scheduled to get underway in 2020. And just like the rat eradication, the removal of mice will likely provide additional, unexpected benefits to other species, such as native plants and insects.

READ MORE: Lead's Impact on Midway's Birds

I arrived on Midway in 2000 as the “albatross catcher” for my wife's Ph.D. research on contaminant impacts on birds. Then, there were more than 100 buildings on Sand Island. In the course of our work, it became obvious that the albatross chicks at nests near buildings had a much higher incidence of a deadly condition called “droop wing,” which caused their wings to drag along the ground and made it impossible for them to fledge.

A simple analysis of the birds' blood — the same approach used to evaluate sources of lead poisoning in children — showed that lead paint peeling off the buildings was the culprit. Like toddlers who tend to put anything in their mouths, the chicks were picking up lead chips from around their nests and ingesting enough paint to poison themselves.

Upon finishing her Ph.D., my wife, Dr. Myra Finkelstein, worked as a Switzer Foundation post-doctoral fellow with ABC's policy team and FWS to find a solution. After years of effort, and with help from Audubon California and the Center for Biological Diversity, Midway was declared a U.S. Environmental Protection Agency Superfund site, and in 2011 an expanded cleanup effort began. In 2018, the lead cleanup was completed. This year, the albatross chicks should all fledge lead free.

— Brad Keitt, ABC's Ocean and Islands Program Director

Planning for Rising Seas

Once mice are removed from Midway, there will no longer be any introduced mammals — the scourge of so many tropical islands worldwide — and the seabirds and other wildlife will have survived one more threat.

But a global challenge remains, one that presents particularly severe risks to islands. FWS biologists are turning their attention to climate change-associated sea level rise, which is already etching away at the atoll's shorelines. The combination of rising seas and more severe storms will inundate nest sites across the Hawaiian archipelago's low-lying atolls, the chain of small islands that arc for more than 1,000 miles to the northwest beyond the main “high” islands of Hawai‘i. We've already seen evidence of dramatic storm damage: In October 2018, Hurricane Walaka completely erased East Island within the Northwestern Hawaiian islands' French Frigate Shoals, eliminating critical nesting habitat for Green Turtles and 2,500 pairs of albatrosses, among other seabirds.

Fortunately, some parts of Midway are high enough to remain above sea level for the foreseeable future. But if sea levels continue to rise, habitat will be lost, both at Midway and on other low-lying islands.

Predator-proof fencing, shown here on Kaua'i, protects seabirds on some of the main Hawaiian Islands. Photo by Ann Bell/FWS.

In response, biologists are eyeing the higher main Hawaiian Islands, hoping to jump-start seabird colonies there. On Oahu, Pacific Rim Conservation has teamed with FWS and others to translocate seabird chicks from the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands to fenced areas. There, “attraction arrays” (decoys and sound systems that broadcast colony noises) hopefully will lure birds — both the fledged chicks, once they reach breeding age, and passing adults — to adopt these new, higher-elevation nesting sites.

On Moloka‘i, ABC is partnering with the Moloka‘i Land Trust and others to use attraction arrays to encourage albatrosses to colonize higher ground at a coastal site. A fence is being built there as well, to exclude introduced predators. ABC's work on Moloka‘i is made possible thanks to the generous support of the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (Coastal and Science Applications Programs), The David and Lucile Packard Foundation, the BAND Foundation, Sacharuna Foundation, and Lynn and Stuart White.

For now, Midway's stewards are doing what they can to maximize the atoll's resilience, while continuing to reduce threats posed by mice and other invasive exotic species. If humanity can curb its carbon emissions and avoid the most-dire sea level rise projections, then there is a chance that much of Midway's wildlife will continue to thrive and — just as it did for me — continue to inspire us to never give up protecting nature.

| Martha Brown is a writer, editor, and field biologist. She lives in Santa Cruz, California. |