Green and noisy, restored island offers hope for Black-capped Petrel

The landing at Desecheo Island requires visitors to leap from a small boat in deep water onto black, volcanic rocks. We had delayed the trip once due to 10-foot seas generated by Hurricane Lee. Today, I was lucky, and our 90-minute boat ride from the west side of Puerto Rico was glassy calm, making the 12-mile crossing quick and the jump onto the island from the small dingy relatively easy. It was an auspicious start to a long-standing goal of attracting Black-capped Petrels to nest on the island.

My first trip to the island, a National Wildlife Refuge (NWR) within the Caribbean Islands NWR complex, was over 15 years ago. That trip precipitated a flurry of visits and activity that resulted in the island becoming free of invasive mammals — rats, goats, and macaques were removed as part of a long-term plan to restore the island's unique flora and fauna. The work wrapped up in 2016, and it had been more than seven years since I had been on Desecheo when I returned in September 2023. This time, I was accompanied by a crew from the Caribbean Islands National Wildlife Refuge; a Puerto Rican business, Effective Environmental Restoration, hired to help manage seabird restoration on the island; and a long-time colleague from Island Conservation whom I worked with on the invasive species removals. We were also accompanied by NWR law enforcement, which is required because the island is closed to the public, a holdover from years of use as a Navy bombing range that left unexploded ordnance across the island.

The history of Desecheo Island is one repeated over and over again on islands around the world. Abundant birdlife, ecological diversity, and unique species found nowhere else are eliminated by the introduction of invasive species — intentional or not — followed by the inevitable collapse of the island ecosystem. This island, Desecheo, went from a veritable seabird paradise to an island nearly devoid of breeding seabirds. Five breeding species, including the world's largest Brown Booby colony, were driven to zero. Only two species still nested — Brown Noddy and Bridled Tern — with a total of fewer than 10 pairs.

When I first visited Desecheo more than 15 years ago, the island was dusty thanks to goats that chewed through the vegetation, leaving the landscape barren. And seabirds were few and far between. I'd occasionally spot a few boobies on offshore rocks, perhaps asking the question, “Is it safe to return?”

I went back to provide a helping hand to the seabirds and to try to start additional recovery. Shortly after the last of the invasive rats were removed from Desecheo, social attraction was implemented to encourage the seabirds to return. Social attraction involves broadcasting the sounds of an active colony over a solar-powered, automatic amplified sound system. For diurnal (daytime) species, decoys, life-size models in different poses — a nesting bird here and a displaying pair over there — are set out to make a bird feel at home. Mirrors can provide a sense of live action when a bird lands and begins its mating dance, none the wiser that its potential mate is only a reflection.

Species that regularly move their nesting sites are the easiest to attract, and terns, gulls, and noddies often respond to social attraction in one to several years. On Desecheo, Bridled Terns responded immediately, and breeding numbers continue to grow. Species that have high site fidelity, such as the tubenoses (petrels and albatrosses), can take much longer to arrive. That is why we were so excited when an Audubon's Shearwater, a species previously unknown from the island, responded to social attraction and began nesting in 2022.

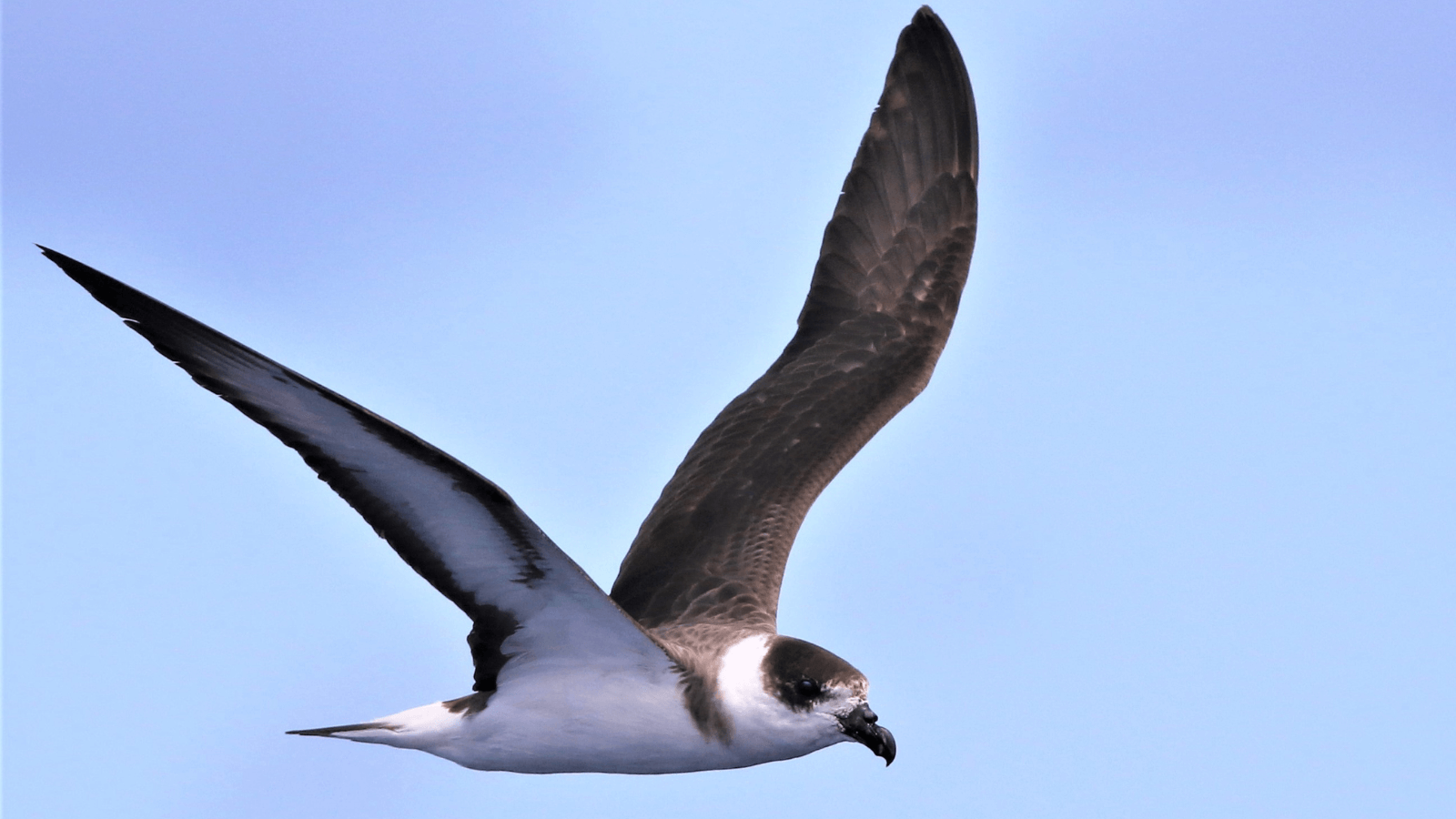

I returned this September to initiate social attraction for another tubenose, the Black-capped Petrel. An Endangered species, the petrel is only known to breed on Hispaniola, the island that is home to the Dominican Republic and Haiti. But Desecheo is along the route the birds take from their nesting grounds to their wider Caribbean feeding territory, and it is possible they might hear the sounds of a colony and go to investigate. If we can establish a new colony on an island free of invasive species, the population could grow rapidly. Similar projects for Atlantic Puffins and Short-tailed Albatross have been wildly successful. If social attraction for Black-caps doesn't work, then in the future we may consider active translocation, where young birds are moved before they imprint on their nesting site and then are hand reared until they fledge. This has worked wonders for dozens of species, including ABC's project with Hawaiian Petrels and Newell's Shearwaters on Kaua‘i.

The first thing I noticed when we approached the island for my return trip was the green. Seven years without invasive mammals had done wonders for Desecheo's vegetation. As we pulled up to the anchor site, I could see through the clear waters to the ocean bottom. I mentioned this to the boat captain, and he told me the dive tour operators have been raving about the increased water clarity around the island — all that vegetation is keeping the soil on the island, making the waters clearer and the surrounding corals healthier. As we loaded up our packs with solar panels, a deep-cycle battery, speakers, and other supplies, it occurred to me that the changes I was seeing on the island were one of scale. When I first visited, you could still find most of the parts that make up the Desecheo Island ecosystem, but you had to be observant and look closely. A booby might have flown by along the shore — not a breeder but a prospective one. An endemic Harrisia cactus might have been 3 inches tall and tucked under a rock at the bottom of a steep cliff. But now, the island speaks loudly. Six-foot tall Harrisia fight for space among other shrubs and vines. Endemic lizards scamper away under foot. In springtime, nesting terns and noddies make a raucous noise.

The other major change I noticed was among the team working on the restoration, including myself. An attitude of hope and anticipation was palpable, replacing fear and regret. Now when I see a booby fly by, or terns and noddies roosting on offshore rocks, I want to yell at them “It is safe!” While this “jump-start” of social attraction is a first step in a long process for recovery of the Black-capped Petrel, things are looking up for Desecheo. I can only hope I get to return to the island in another seven years to see what else is nesting and how the island continues to recover.

This work was funded in part by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service.