New Hope for Hawaiian Petrels, Wandering Souls of the Sea

On my first night searching for the Hawaiian Petrel, I am wrapped in a sleeping bag in a lava field at 9,500 feet, waiting. The Milky Way above me is a river of stars. As I watch for the nocturnal seabirds to arrive under cover of darkness between dusk and midnight, I wonder: Will they appear?

“Bird!” my research partner calls. I scurry as fast as I can over the lava rubble on the edge of Haleakala Crater to a nest illuminated by a small piece of reflective tape. Cold rock resembling a barren moonscape might seem inhospitable, but the petrels have chosen this place—free from human harassment and, most importantly, protected from predators—to nest.

Centuries ago, Hawaiian Petrels likely numbered in the hundreds of thousands to millions of birds. Today, the species is one of Hawai'i's most endangered seabirds. Photo by Jim Denny / kauaibirds.com

We are here to measure the movements of this chick-rearing adult and recover a solar-powered tag that has been on the bird for 15 days. We have to be quick: A bird disturbed for too long may fail to feed its chick. And for this population of rare birds to survive, each chick is precious.

The bird is quiet in my hand. Small and stout, with dark upper wings, a white forehead, and large, expressive eyes, it has just arrived from the sea. Its smell is distinctive: a mix of musk, ocean spray, and squid. Like their larger albatross cousins, Hawaiian Petrels fly thousands of miles to forage for food, which they distill into a nutritious slurry of fish and squid oil to feed their chicks.

I hold the petrel gingerly as my partner removes the small solar satellite transmitter, weighs the bird and returns it to its rocky crevice and chick.

Wailing Spirit Birds

Ancient Hawaiians described Hawaiian Petrels as wailing souls wandering the night, with distinctive calls—“ooh aah oooh”—that inspired a short, simple Hawaiian name: 'Ua'u. From coast to mountains on all eight of the main Hawaiian Islands, these ethereal sounds once filled the night sky.

A Hawaiian Petrel against the night sky. Ancient Hawaiians named the bird 'Ua'u for its distinctive calls. Photo by Jonathan Felis / U.S. Geological Survey

We can only guess at the past abundance of 'Ua'u prior to the arrival of the first Polynesians, but it was likely in the hundreds of thousands to millions of birds. Today, the 'Ua'u, or Pterodroma sandwichensis, is one of Hawai'i's most endangered seabirds.

Numbering an estimated 10,000 breeding pairs and thought to be declining, the birds are now restricted to the highest peaks and most remote wet mountain forests on five islands. Facing a litany of threats in recent decades—invasive species, power lines, lights, and habitat loss, to name a few—this elusive species has struggled to survive.

But collaborative conservation efforts over the past few decades by scientists, private landowners, advocates, energy companies, and even resort owners may be slowly turning the tide. New research and tools are telling us more about this charismatic seabird and helping us find ways to protect it.

Scientists who have dedicated their whole lives to studying a bird they rarely see on land now say with guarded optimism: If we stay the course, the endangered Hawaiian Petrel will make a comeback.

Threats on Land from Invasive Species

Although researchers have studied the Hawaiian Petrel for nearly 50 years, the bird is still something of a mystery. Because they forage at distant feeding areas and nest in remote underground burrows, we don't know the bird's absolute population size or the reproductive success of various colonies. Nor do we know the full impact of threats at sea from bycatch, climate change, and marine plastics.

The Hawaiian Petrel is still something of a mystery to scientists. Photo by Jim Denny / Kauaibirds.com

On land, however, threats to the Hawaiian Petrel are all too evident. Over the past two centuries, vast tracts of native bush have been transformed into agricultural land. It wasn't until the late 1960s and early 1970s that scientists began to realize the non-native plants and animals that accompanied human settlers were just as devastating as changes to the land.

Feral pigs, dogs, rats, and mongooses have since resulted in the voracious predation of native land and sea birds. But of all the introduced predators, cats are by far the greatest threat to the petrel's breeding colonies, according to André Raine of the Kaua'i Endangered Seabird Recovery Project (KESRP).

Optimism for the petrel's future is no easy feat for Raine, who has the sobering job of finding adult birds killed by cats outside of their nesting burrows. But there is reason for hope.

“Having well-identified solutions to counter the threat of predators—and the buy-in from partners to deal with these issues—makes me cautiously optimistic for the recovery of this species,” Raine says. “We can now get started to reverse some of these trends.”

In 2014, ABC and Pacific Rim Conservation, working with the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, built a predator-proof fence at Kilauea Point National Wildlife Refuge. Last month, 10 petrel chicks were relocated to this area, called Nihoku, to establish a new colony. This month the last of this first cohort of petrel chicks fledged, marking the beginning of the new direction for this species. (Read more about the translocation and the chicks' time at Nihoku.)

A Hawaiian Petrel chick shortly after being moved to the Nihoku site in November. Photo by George Wallace / American Bird Conservancy

Obstacles to Petrel Recovery

Wind turbines, lighted structures, and power lines present other obstacles for the petrels. Unaccustomed to large structures and lines in their habitat, petrels accidentally collide with them along their sea-to-land flyways.

Light provides another challenge: Petrels and other nocturnal seabirds are attracted to street lights, lighted buildings, and hotel spotlights and become stunned, flying in circles until they land on the ground.

Emerging from their underground burrows on their first flight from mountain nest to the sea, chicks are most vulnerable. Unable to perceive obstacles because their sensitivity to contrast is low, the young birds become disoriented. The momentary lapse in vision from bright lights, combined with power lines, is often fatal. Once grounded, they can be crushed by cars or eaten by predators.

A Hawaiian Petrel fledgling just outside its burrow in Haleakala National Park, on the island of Maui. Photo courtesy of Haleakala National Park

That's where the Kaua'i Humane Society's Save our Shearwaters Program comes in. During September through December, volunteers collect, rehabilitate, and safely release grounded shearwaters and petrels.

Based on this work, there is good and bad news. On the one hand, the volunteers are saving many birds. On the other, they are finding far fewer chicks, which indicates ongoing population declines on this island.

New Tactics and Good News

Despite these dangers, there is one place where the petrels are now thriving: Maui's Haleakala National Park. Progress has been hard-won, reports Cathleen Bailey, Supervisory Wildlife Biologist and the park's lead on the species, who has been studying the petrels for the last 20 years.

Bailey says that numbers are heading in the right direction. In 1966, there were 15 known burrows at Haleakala. Today's robust colony now has between 3,000 and 4,000 burrows (10,000 petrels). She credits a long-term commitment to fencing and predator control, begun in the late 1970s, with the population increase.

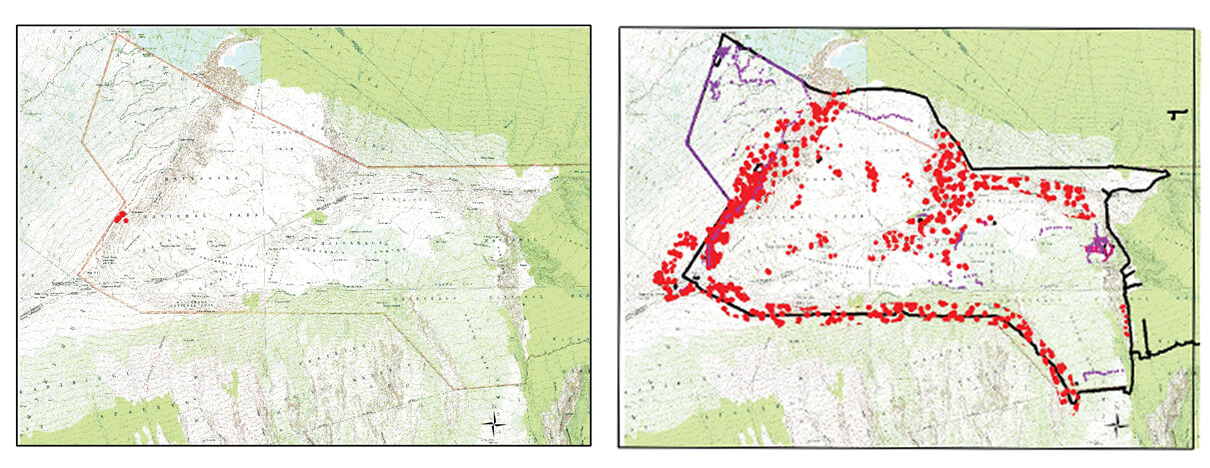

In the 1960s, only a very few Hawaiian Petrel burrows, marked with red dots, existed within Haleakala National Park (above left). Decades of fencing and predator control have resulted in a significant increase today (above right). Map courtesy of Cathleen Bailey / Haleakala National Park

On Kaua'i, where there are only a few hundred known nest sites and numerous threats, the story is different. KESRP's approach is to protect sites where they have found nesting birds, and scout for new sites using technology such as camera traps and acoustic monitoring.

New tools are key: In 2015 KESRP monitored petrel colonies at five priority sites using high-tech equipment such as burrow cameras and acoustic monitoring devices. And there is a growing commitment among landowners, utility companies, and resorts to find ways to reduce threats to the Hawaiian Petrel.

A Future for the 'Ua'u?

Back at Haleakala, we have accomplished our mission and are ready to return to civilization. As we hike out of the petrel colony, we see hundreds of cars in a stream of headlights stretching all the way up the great mountain, zig-zagging up switchbacks to see the famous sunrise over the crater rim. These people will probably never have the incredible experience of holding a seabird in their hands. I doubt any of them even know this bird exists.

Getting people to see and appreciate endangered Hawaiian seabirds is a major challenge. For most people, these are ghost birds, only heard occasionally at night at the right place.

It's nearly 5 a.m. by the time we drive back to the bunkhouse and dive into a dark-shuttered room to sleep. Visions of birds and starry skies fill my dreams.

Does the 'Ua'u—the wandering soul of the sea, so elusive, yet so inspiring to those who know it—have a future? All signs point to a tentative, hopeful “yes.”

Editor's note: A longer version of this story first appeared in the spring 2015 issue of Bird Conservation magazine.

Hannah Nevins is ABC's Seabird Program Director. She has nearly 20 years of seabird conservation experience, ranging from the clearing of non-native rats on nesting islands to assessing impacts of gill nets. She managed the response program at the Marine Wildlife Veterinary Care and Research Center at the California Department of Fish and Wildlife, was founding board member of Oikonos Ecosystem Knowledge, and is active in the Pacific Seabird Group. Hannah received an MSc in Marine Science from Moss Landing Marine Laboratories/San Francisco State University.

Hannah Nevins is ABC's Seabird Program Director. She has nearly 20 years of seabird conservation experience, ranging from the clearing of non-native rats on nesting islands to assessing impacts of gill nets. She managed the response program at the Marine Wildlife Veterinary Care and Research Center at the California Department of Fish and Wildlife, was founding board member of Oikonos Ecosystem Knowledge, and is active in the Pacific Seabird Group. Hannah received an MSc in Marine Science from Moss Landing Marine Laboratories/San Francisco State University.