To Sail Like a Seabird: How Wind and Waves Link Sailors, Surfers, and Seabirds

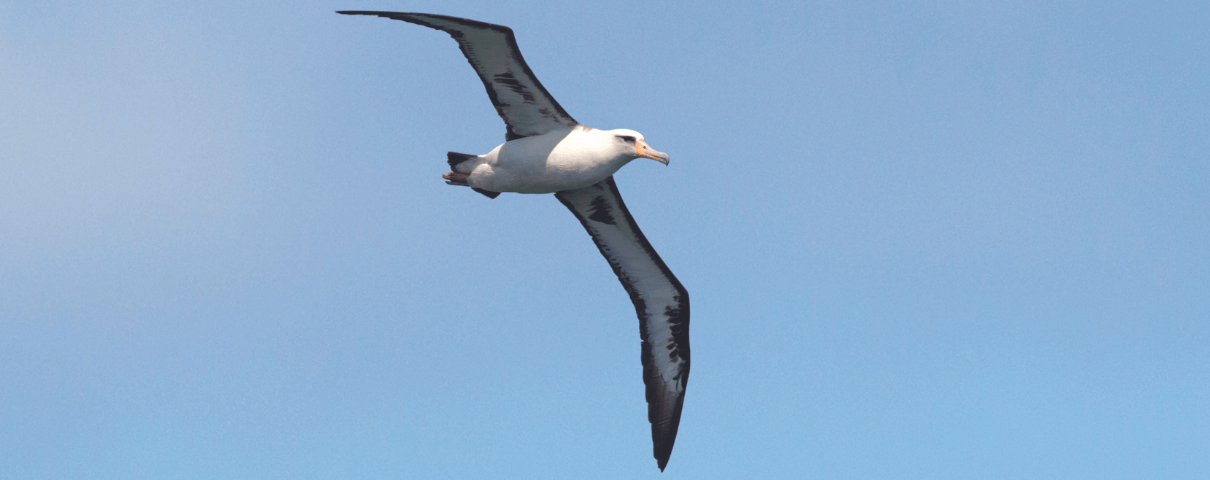

Many people have heard of albatrosses, but mariners and aviators have a special affinity for these ocean-living birds and their amazing abilities. Consider this: A Wandering Albatross can circumnavigate the Antarctic three times in a year, and travel over 3,100 miles in a week with very little energy expenditure. Or how about this: A Laysan Albatross nesting in Hawai'i can provision its chicks by foraging in Alaska.

How can a bird that weighs on average 16 pounds, in the case of the Wandering Albatross, skim over large portions of the globe with ease? Two words: dynamic soaring. Dynamic soaring is a complex mechanism by which seabirds utilize wind shear — the variation in wind speed above the ocean surface — to extract energy and fly without flapping, with virtually no energy cost to themselves. The result is an arcing flight pattern during which the bird gains altitude by soaring into the wind, banks vertically in the stronger wind 10 to 30 feet above the surface, then drives downward with increased velocity to carry it toward its destination, before turning into another upwind maneuver farther along, then repeating the process. Albatrosses could not do what they do — in essence, could not exist — without this capacity.

The marvelous flight of albatrosses and other seabirds runs like a thread through my life, not just because I dedicate my professional life to conserving these creatures, but because they inspire me, as they have many others through the years. My hope is, too, that they will always be around, and the link between mariners and marine birds may be a tie that helps make this possible.

Timeless Wonder

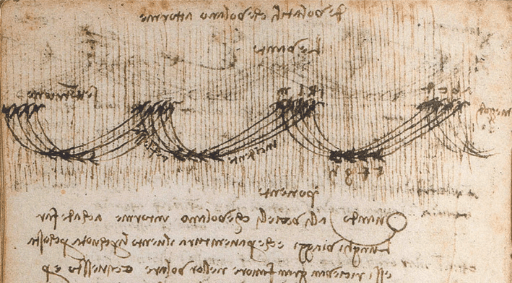

People have been marveling at seabirds, especially the larger ones, for centuries. Nobel physicist Lord Rayleigh is often cited as the first to describe dynamic soaring in birds, and indeed he was the first to publish a model of the process in 1883.

Centuries earlier, though, Leonardo da Vinci also pondered this process. Only recently did it come to light that buried within da Vinci's codex on bird flight were drawings and descriptions of flight patterns and the processes underlying them that are consistent with dynamic soaring. Through observations of flying birds, both da Vinci and Rayleigh gained insight and inspiration, suggesting that the ability to extract energy from the wind would bode well for the prospect of human flight. Today, complex models emulating seabird dynamic soaring are being used to inspire wind-powered, autonomous drones that could collect valuable oceanographic data.

Harnessing the Wind

For me, observing seabirds provides constant inspiration and has helped me learn to “fly” as a sailor. My father gifted me the skill set to harness the power of wind and wave, while sharing with me his two great passions, sailing and birding. He developed these interests between the ages of 10 and 13 in Madison, Wisconsin. Dad learned to sail on Lake Mendota, eventually graduating to the large sailing dinghies called E Scows. While exceptionally fast in flat water, these boats did poorly when waves began to build. It wasn't until after college, while living in Massachusetts, that Dad began to observe seabirds and started to emulate their movements over water.

I grew up in north-central Florida, surrounded by lakes and equidistant between the Atlantic and Gulf Coasts. I initially took to sailing much more than birding, perhaps because birding was what my older brother did. My father's favorite sailing location was Cedar Key, on the Gulf Coast, a little over an hour's drive from home. There, he found ample access to open water where the fetch — the distance wind travels over open water — allows waves to build and a Sunfish sailboat to undulate up and down, extracting energy from the wind and waves so it and its operator can fly across the water.

I recall many afternoons at Cedar Key, which I spent clinging like a barnacle to the foredeck of my father's Sunfish, balanced precariously between sheer delight and fear. My father's skill at allowing the delight to overcome the fear is something I am trying to capture as I begin exposing my twin 10-year-old boys to my water-sport passions.

A Sailor's Epiphany

Around the time I was born, my father began the first of several summers on the coast on Cape Cod, at Cotuit, Massachusetts. There, a 14-foot, flat-bottomed, crab-claw-rigged Sunfish dinghy was at his disposal. It was reading his recollections of those experiences that led me to consider my own seabird/sailing connection.

Reflecting on the summer of 1967, Dad wrote: “I cleared Dead Neck in Cotuit Bay and headed out into the Sound where the 3- to 4-foot waves rolled in on steady 15-knot winds all the way from Block Island. I found that the dimensions of the Sunfish fit me perfectly. I could control the rudder from the exact midpoint of the hull by a long tiller extension. I could tuck my toes under the far edge of the cockpit and lean far out over the water when required. As I moved rapidly out of sight of the low dunes, the waves built up and needed to be dealt with. With the wind also rising, the carefully shaped hull of the Sunfish lifted beyond the depth dictated by its buoyancy. This high speed and precarious state between sailing and flying is called planing. A miracle happens.”

My father was basically avoiding broadsides from roiling whitecaps by surfing down the face in front of the wave and then back up it to ride the unbreaking swell, until a whitecap formed again. This must have been one of my father's most thrilling days of sailing. He drew parallels to surfing, and also hinted that there seemed some parallel with the movement of seabirds.

He continues: “Some albatrossian intuition seemed to be guiding me to broad-reach with the waves on a plane until the moment the following crest begins to break. Then a quick pull on the tiller and slack of the sail drops the boat rapidly downward. Just before plowing into the next wave, a shove on the tiller and a rapid haul-in of the sail power the boat back up to ride the next wave in the line. An aerial observer (perhaps an amused albatross) would witness a wildly gyrating sailor, zigzagging across wave and wind shrieking with pleasure. I believe I made it halfway to Nantucket on that day.”

It would be another 15 years, though, before my father made the intuitive link between these actions and dynamic soaring in open-ocean seabirds. That happened with the fortuitous find of a book by the British naval officer Sir William Jameson, entitled The Wandering Albatross. This monograph, which, according to the ornithologist Robert Cushman Murphy, contains the best nontechnical description of dynamic soaring flight, was inspired by Jameson's observations of this species in the southern oceans starting in 1940, during the hunt for the German battleship Admiral Graf Spee. It was by reading this book that my father made the connection between the movement of the Sunfish in a modified S pattern and that of the albatross.

Different Path, Same Dynamic

As Dad's sailing evolved to parallel albatross flight, I gravitated toward windsurfing, which I picked up in high school because it was an easily transportable, individual activity I could do on my own on Florida's lakes and coasts. I recall that when I applied and eventually matriculated to the University of California, I was only slightly aware that Santa Cruz, California, is recognized as the best windsurfing destination in the continental U.S. I can admit to being slightly more aware of the fact that studying seabirds might mean a life in and around the ocean as I began to consider a potential career path using my degree in biology.

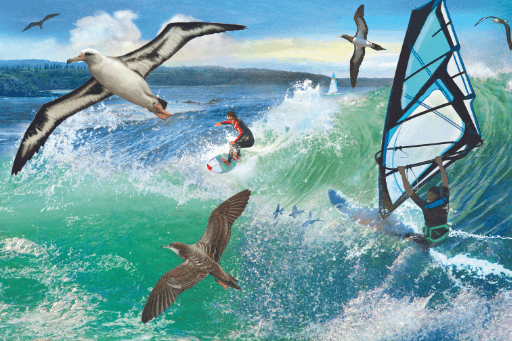

It was here, on the edges of Monterey Bay, that I was able to truly observe dynamic soaring. While it usually takes a pelagic trip to get far enough out to see Black-footed and Laysan Albatrosses, it is possible to be surrounded by Sooty Shearwaters while sailing at certain coastal sites around Santa Cruz. Watching these birds effortlessly glide down the waves and navigate wind gusts provides endless entertainment, but also helped me learn how to be a better sailor.

Although I've traveled the world to work on their nesting islands, it is while sailing that I feel most in tune with seabirds, perhaps because a windsurfing sail is about as close as you can get to an albatross wing. An albatross can travel upwards of 40 miles an hour during dynamic soaring, sometimes twice the speed of the wind. On a windsurfer, I can reach about 20 miles per hour, or 25 if really trying in strong winds of equal speed. But it is lighter-wind days that require the most skill, drawing from all I have learned from watching seabirds. On these days, by utilizing slight variations in wind speed and direction, and surfing the wind swell to stay on a plane, it is possible to move faster than the wind, essentially creating your own “apparent” wind to fly over the water.

Steering Seabirds From the Doldrums

Unfortunately, there are fewer and fewer opportunities for sailors to watch and learn from seabirds, as many species are in decline around the world. On Maui, the undisputed windsurfing capital of the world, albatrosses are unable to breed due to introduced invasive mammals, disturbance, and other factors. You can still see the occasional Wedge-tailed Shearwater glide over the water, and the flapping flight of boobies just offshore. Exciting, yes, but a far cry from what a true, undisturbed seabird nesting island would offer.

ABC has been working with partners at the Maui Nui Seabird Recovery Project to create seabird sanctuaries around the island. This builds on successful and in-progress projects across the Hawaiian Islands, and involves building fences to exclude nonnative predators and restore seabird breeding colonies. Steps are being taken to encourage birds to return to nesting areas on their own. These include putting out painted fiberglass bird statues as decoys to attract diurnal species, and artificial burrows for nocturnal birds. Then sounds of an active colony are broadcast via speakers. For some species, an effective approach is to translocate chicks from unprotected nests to artificial ones within the fence.

Restoring seabirds to Maui, and islands around the world, provides far more than just inspiration for sailors and water-sports enthusiasts. Seabirds provide an important link between marine and terrestrial habitats by transporting nutrients — mostly in the form of guano deposited on the islands — from the ocean to land. This drives productivity on land, supporting plant and insect diversity. Seabird-derived nutrients are transported via rainfall and runoff into nearshore environments, which are critical sites for fish reproduction and coastal resiliency. These nutrients are incorporated into corals, sea grasses, and plankton. Recent data show that islands with healthy seabird populations support coral growth that is twice as fast as on islands without seabirds, and that these corals are more resilient to increasing ocean temperatures.

Dr. Sheldon Plentovich, Pacific Islands Coastal Program Coordinator for the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and a former professional kite surfer, says: “Nesting seabirds are vital to healthy coastal ecosystems. But they are also ambassadors helping link oceans to land and people to the natural world. When I am on the water, I strive to mimic the graceful lines drawn by the albatross, and my hope is that more people will have the chance to experience the grace, devotion, and charisma of albatrosses as they begin to nest in proximity to humans on the high islands of the Hawaiian archipelago.”

It seems the albatross are ready to return. A Laysan Albatross was seen on the North Shore of Maui in January 2021, the first observed on the island in more than a decade. With some help, it is very likely that albatrosses will once again be flying in the waves just off Maui, coming ashore to breed, and in the process, closing the loop between land and sea and sailor and seabird.

The forces that enable dynamic soaring will always be with us. My hope is that albatrosses and other seabirds will be as well, serving as tutors for future generations of sailors, just as they did for my father and me.

| Brad Keitt is ABC's Oceans and Islands Program Director. He has conducted research on all of the Baja Pacific Islands, as well as islands in Alaska, Hawaii, California, the tropical Pacific, and the Caribbean. Brad was a founding member of Island Conservation. |