Scientists Try A Daring Approach to Save Endangered Hawaiian Petrels

On a rugged ridgeline high in the mountains of Kaua‘i, a helicopter touches down on a small platform. Three wildlife biologists climb out and begin hiking across steep slopes cloaked with ferns and wind-stunted trees.

The mountain forests in Hawai‘i's Hono O Na Pali Natural Area Reserve are usually damp and obscured by a bank of clouds, but on this early November day, the sun is shining and the air is warm. The scientists marvel at the good weather.

Hawaiian Petrels breed high in Kaua‘i's mountains, but their burrows are vulnerable to non-native predators. André Raine/Kaua‘i Endangered Seabird Recovery Project

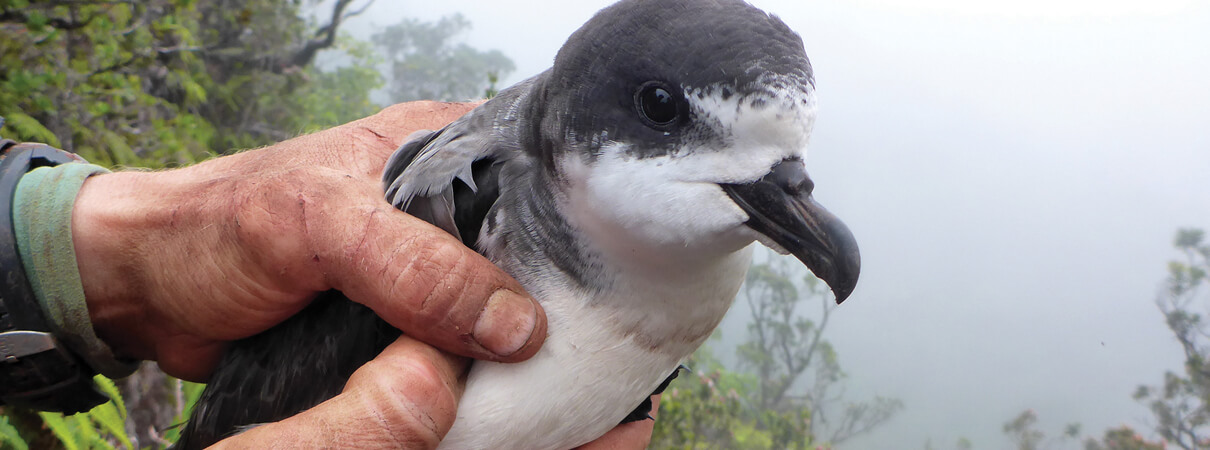

After 15 minutes the team stops in front of a small hole gouged out of the mountainside. André Raine, coordinator of the Kaua‘i Endangered Seabird Recovery Project, reaches into the burrow with one arm, feeling around for the plump Hawaiian Petrel chick he knows is inside. Gently guiding the young bird toward the opening—he doesn't want its delicate wing feathers to snag on a root—Raine slowly removes the chick.

Cradled in the biologist's hands, the chick regards the alien landscape around him. Gray and fluffy, with ungainly webbed feet, the bird's downy feathers rustle in the breeze. Raine pauses for only a moment before placing the bird in a plastic pet carrier.

The conservationists must work quickly. They are on this mountaintop to take endangered Hawaiian Petrel chicks away from an area where they are vulnerable to non-native predators and establish the birds in a haven on the coast. Their task is risky. Each Hawaiian Petrel chick is important to a declining population. Should anything go wrong—a bird overheats, or dies because of stress or injury—it would only undermine the goal of this pioneering conservation effort.

Andre Raine of the Kaua‘i Endangered Seabird Recovery Project holds a Hawaiian Petrel chick after removing it from its mountain burrow. Raine is part of a team of biologists working to save the endangered bird from extinction. Photo by Mike McFarlin/Kaua‘i Endangered Seabird Recovery Project

Yet for the biologists, who've been working for years toward this moment, the hope outweighs the danger. If they succeed, it will be a significant new chapter in work to save Hawai‘i's seabirds. Not just for this species, and not just on this island—but for seabirds across the state on the verge of extinction.

'A Radical Intervention'

The Hawaiian Petrel—known as ‘Ua‘u for its ethereal nighttime calls—was once Hawai'i's most abundant seabird. From mountain peaks to coastal cliffs, the birds congregated in large breeding colonies, arriving by night to dig burrows with their beaks and the claws of their webbed feet. Fishermen looked to the petrel as a sign of tuna foraging just beneath the ocean's surface. The guano of millions of petrels fertilized Hawai‘i's forests with phosphorus and nitrogen from the sea.

Faithful to their nesting sites, the birds return to their burrows year after year—even if their chosen spots are vulnerable to predators or development. Cats, rats, and pigs eat the birds in their remote mountain burrows. Power lines and bright lights jeopardize the birds' frequent flights to and from the sea. In recent decades, the seabird's population has plummeted.

The Hawaiian Petrel was once Hawai‘i's most abundant seabird, but is now listed as endangered under the federal Endangered Species Act. Photo by Cameron Rutt

Yet if the petrels' nesting habits have made them susceptible to harm, they are also proving to be a valuable tool in engineering a comeback for the species. Using a technique borrowed from conservationists in New Zealand, a nation whose native birds are similarly threatened by invasive species, a team of conservation groups and government agencies has worked since 2011 to create a new colony of Hawaiian Petrels in an area designed for them to thrive.

The collaborators—including Pacific Rim Conservation, the Kaua‘i Endangered Seabird Recovery Project, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, and American Bird Conservancy—are trying a daring and novel approach. They are moving chicks of an endangered seabird to a protected area in time for the fledglings to imprint on the new site, with the hope that the birds will return there to breed. The young petrels will be the founders of the only fully protected colony of federally listed seabirds anywhere in the Hawaiian Islands.

“A translocation like this is something people have talked about in Hawai‘i for many years, for decades, really,” says Eric VanderWerf, President of Pacific Rim Conservation. “But it hasn't happened until now.”

Hawaiian Petrels spend their first few years of life living over the open ocean. They return to land to breed. Photo by André Raine/Kaua‘i Endangered Seabird Recovery Project

With innovative techniques such as translocation, conservationists can work to check the losses that have earned Hawai'i a reputation as the bird extinction capital of the world, says ABC's George Wallace, Vice President of Oceans and Islands.

“It's quite a radical conservation intervention,” he says. “But this is the kind of stuff we have to do. And if we don't, we are going to lose species.”

Seven Acres of Safety for Hawaiian Petrels

A small army of people began work on this project long before the helicopter ferried biologists to the mountains on that warm November day. The logistics amounted to an exhilarating but head-spinning plan, requiring 16 state and federal permits and 600 pages of detailed documentation.

With the help of the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, the partners selected an appropriate site at Kilauea Point National Wildlife Refuge. Pacific Rim Conservation then oversaw the construction of a predator-proof fence around the site. Within the enclosure, Pacific Rim removed rats, mice, and other predators; installed 50 artificial burrows; and cleared invasive plants and restored native vegetation on a portion of the enclosed area to make the site hospitable to the seabirds. Meanwhile, over four years the Kaua‘i Endangered Seabird Recovery Project worked to identify and monitor burrows high in the mountains from which chicks could be taken.

A predator-proof fence makes the 7-acre enclosure at Nihoku safe for the petrels and other seabirds. Photo by Jessica Behnke

Known as Nihoku, the site at Kilauea Point is roughly seven acres on a section of the refuge closed to the public. The fence keeps out all predators, even mice. A gradual slope toward the ocean cliffs below, and the site's orientation to the trade winds, will give the fledgling petrels a straight shot to the ocean.

Having the enclosure on a National Wildlife Refuge means that “we're going to have conservation in this area in perpetuity,” says Michael Mitchell, Deputy Project Leader at Kilauea Point. “Those birds are going to be here for many generations to come.”

Down from the Mountain

Back on the mountaintop, six biologists working in two teams spend several hours going from burrow to burrow. The portly birds—aside from a few pecks at human hands—are mostly calm as they journey by helicopter to the coast.

Megan Vynne of the Kaua‘i Endangered Seabird Recovery Project makes her way across the mountain ridge to the helicopter that will ferry the chicks (in blue carriers) to the coast. Photo by Lindsay Young/Pacific Rim Conservation

With a petrel carrier on his lap, Raine watches the lush, green valley glide by below. He can hear some of the birds shuffling in their boxes. It's a peculiar experience for the fledglings, he thinks. Since hatching, they have known only the cool, dark interior of their underground burrows. Now they're on a voyage to a new home.

“I can't believe this has gone off without a hitch,” he thinks to himself.

After landing at a small airport on the coast, the birds go straight to Nihoku by car. There, avian ecologist Robby Kohley and avian care specialist Marilou Knight, both with Pacific Rim, will care for the birds until they fledge. As soon as the birds arrive, Kohley measures and weighs them before placing each bird in its burrow.

With the birds safely ensconced in their new dwellings by early afternoon, the exhausted biologists head to a nearby coffee shop to refuel. Bringing the chicks in from the mountain—without incident—was a triumph, they feel. Proof that translocation can be done in Hawai‘i.

Artificial burrows at Nihoku are situated on a gradual slope toward the ocean cliffs below. The site's orientation to the trade winds will give the fledgling petrels a straight shot to the ocean. Photo by Robby Kohley/Pacific Rim Conservation

“It's the start of a new era in seabird conservation,” Lindsay Young, Executive Director of Pacific Rim, says later. “We've created a new home for a species that desperately needs it.”

But the work is hardly over. Young, feeling the anxiety of sudden parenthood, sleeps little that night. When she awakes early the next morning, she hopes the birds are still alive.

‘As Fast as the Wind Will Take Them'

Caring for the Hawaiian Petrel chicks becomes Kohley and Knight's round-the-clock job. They prepare food, record data, and clean—so much that Kohley starts referring to himself as a bird janitor.

Every day, Kohley and Knight feed the chicks a freshly made slurry of fish, squid, Pedialyte, and vitamin supplements. They watch the birds closely: The chicks are high-strung and feisty, and their behavior, weight, wing length, and appetite all provide a glimpse into their health and growth. (Only one chick struggles: Six days after the birds arrived, No. 5 dies of a bacterial infection apparently contracted before biologists moved her from her mountain burrow.)

Marilou Knight, left, and Robby Kohley, both of Pacific Rim Conservation, measure and weigh each Hawaiian Petrel chick before placing it in its new burrow at Nihoku. Photo by Ann Bell/U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service

As the chicks get closer to fledging, the feeding becomes a balancing act. Kohley wants them light and hungry enough to fly away, but with enough fat reserves to carry them over until they find that first meal.

The chicks come out of their burrows at night to exercise their wings with frenzied flaps. They also memorize the constellations: Celestial cues will help them find their way back. Years will pass before the birds return to this spot, using their mental star maps to find the way.

Kohley is captivated by the birds. “They look a little goofy, but if you see them out at sea where they belong, it's like nothing else,” he says. “They're just as fast as the wind will take them.”

The Sea and the Stars

Ten days after the birds arrive, No. 2 and No. 4 are the first to go. “Our first two chicks fledged from Nihoku last night!” Young writes in an email to partner organizations.

By mid-December, all nine birds have fledged. They will live over the open Pacific Ocean for the next three to five years. Soaring on the winds for thousands of miles, and sleeping on the water, they will use keen eyesight and a sharp sense of smell to find squid and other favorite foods. If petrels can survive their first few years at sea, scientists speculate they have a good chance of living for 30 or even 40 years.

Years will pass before the petrels return to Nihoku, using the constellations to guide the way. Photo by Jonathan Felis/U.S. Geological Survey

As the petrels travel across the ocean, the work at Nihoku goes on. The process to secure state and federal permits is already under way for another translocation this fall of up to 20 more Hawaiian Petrels and 10 Newell's Shearwaters. In time, the partners hope to move roughly 40 seabirds every year to the protected site, while also attracting new avian residents with recordings of seabird calls.

If all goes as planned, success will come on a spring night several years from now. A small, dark bird with a powerful homing instinct will remember the smell of Nihoku. Guided by the stars, the bird will return to this spot—a place it recognizes as home.

This article first appeared in the spring 2016 issue of Bird Conservation.

Editor's note: The translocation of 10 Hawaiian Petrel chicks in November 2015 involved years of planning and coordination from many organizations and agencies: Kaua'i Endangered Seabird Recovery Project, a Hawai'i Department of Land and Natural Resources' Division of Forestry and Wildlife (DOFAW) project administered by Pacific Cooperative Studies Unit, University of Hawaii; Pacific Rim Conservation; the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Kilauea Point National Wildlife Refuge; and American Bird Conservancy (ABC). Kaua'i Island Utility Cooperative and DOFAW supported predator control within Hono O Na Pali Natural Area Reserve. The National Tropical Botanical Garden provided important assistance with vegetation restoration at the translocation site. The National Fish and Wildlife Foundation and ABC provided critical funding support.

Libby Sander is Senior Writer and Editor at American Bird Conservancy. She spent 13 years as a journalist before coming to ABC. She covered a variety of beats in Chicago and Washington, D.C., writing news stories and award-winning features for The New York Times, the Washington Post, and The Chronicle of Higher Education. You can follow her on Twitter at @libsander.

Libby Sander is Senior Writer and Editor at American Bird Conservancy. She spent 13 years as a journalist before coming to ABC. She covered a variety of beats in Chicago and Washington, D.C., writing news stories and award-winning features for The New York Times, the Washington Post, and The Chronicle of Higher Education. You can follow her on Twitter at @libsander.