Avian Superhighways: The Four Flyways of North America

Each spring and fall, North American skies fill with billions of birds in one of nature's most spectacular shows: avian migration. The sheer number of travelers is staggering, but there is an order to the chaos.

Birds navigate along more or less regular routes when they migrate. In North America, these “avian superhighways” are generally grouped as the Atlantic, Mississippi, Central, and Pacific Flyways.

On cross-country flights, migratory birds gravitate toward efficient paths with plenty of rest stops. Some species stick to the coasts, while others plot courses over inland wetlands or follow lengthy natural features like the Mississippi River or mountain ranges. (Even when weather causes them to deviate, their navigation abilities usually help them wind up at the same place each year.)

It's important to note that “flyways” describe broad, generalized pathways; they are not rigid or narrowly defined routes, nor are they used by all migrating birds.

While ducks and other waterfowl are especially likely to use specific paths within one of the four named flyways, the boundaries between flyways can be fuzzier for songbirds.

Some of North America's migratory birds even buck the trend and blaze very different trails. They plot bold journeys over the open ocean or migrate south by one route and north by another. New tracking technologies are giving researchers better insight every year into these incredible journeys.

Understanding flyways can be helpful to anyone hoping to learn more about the wonders of bird migration. Below is an introduction to North America's four basic migratory routes, examples of the birds that use them, and some great spots to experience migration along each flyway. Finally, we've provided some useful information about flyway "rule-breakers."

Atlantic Flyway

Stretching from Florida to Greenland, the Atlantic Flyway contains all of North America's Atlantic Coast. Many birds that use this flyway winter in the Caribbean or South America. To the east, it is bounded by the ocean, and to the west it is roughly flanked by the Appalachian Mountains. However, these borders aren't exact; many “tributary” routes branch off of the Atlantic Flyway, with some birds flying across open ocean or taking journeys that intersect with the Mississippi Flyway to the west.

The Atlantic Flyway has a particularly dense concentration of shorebirds and waterfowl that take advantage of the salt marshes and mudflats along the coast.

In the spring, shorebirds like Red Knots stop in the Delaware Bay area to fuel up on horseshoe crab eggs. Inland, a wide variety of songbirds that winter in Central America, like the Cerulean Warbler and Wood Thrush, capitalize on forested areas for shelter and a quick snack.

Some great places to view this flyway's migrants include Dry Tortugas National Park in Florida; Blackwater National Wildlife Refuge in Maryland; Central Park in New York City; Cape May, New Jersey; Acadia National Park in Maine; Lac Saint Pierre in Quebec, Canada; and Magee Marsh Wildlife Area in Ohio (lower Great Lakes sites are generally considered part of the Atlantic Flyway).

Mississippi Flyway

Many birds using the Mississippi Flyway spend their winters in South and Central America, then travel northward along the Gulf of Mexico before following the Mississippi, Missouri, and Ohio Rivers. The upper portions of the flyway include much of the Great Lakes region and inland northeastern Canada.

An abundance of rivers and lakes makes the Mississippi Flyway an ideal route for ducks, geese, shorebirds, and other waterbirds. These include the Canvasback and Least Tern. Many other kinds of migrating birds take advantage of the forests and riparian habitats of this region as well, including the Prothonotary Warbler and Yellow-billed Cuckoo.

Some of the best spots to see migratory birds along this flyway are Wapanocca National Wildlife Refuge in Arkansas; Reelfoot National Wildlife Refuge in Tennessee; and Trempealeau National Wildlife Refuge in Wisconsin.

Central Flyway

The Gulf of Mexico coastline is also the first U.S. stop in spring for northbound Neotropical migrants following the Central Flyway. From there, they forge a different path through the country's interior. The Central Flyway runs through Texas, Kansas, Colorado, Wyoming, and Montana, extending into the Great Plains and the Prairie Pothole Region (sometimes called the “duck factory”). It is bounded on the west by the Rocky Mountains.

More than 50 percent of North America's migratory waterfowl use this flyway, as well as many shorebirds like the Snowy Plover. The most famous Central Flyway migrant, however, is the Sandhill Crane, a species that gathers in the hundreds of thousands in the Nebraska Sandhills each spring in one of the country's greatest natural spectacles. These birds, which are three and a half feet tall and sport a six- to seven-foot wingspan, stop along an 80-mile stretch of the Platte River to fuel up on grains before flapping on to Canada, Alaska, and northeastern Siberia.

Some top places to witness migration along the Central Flyway include Quivira National Wildlife Refuge in Kansas; Lillian Annette Rowe Sanctuary in Nebraska (for cranes); Barr Lake State Park in Colorado; Freezeout Lake Wildlife Management Area in Montana; and Bosque del Apache National Wildlife Refuge in New Mexico.

Pacific Flyway

The Pacific Flyway runs along the Pacific Coast of North and South America, with some migratory birds flying as far south as Patagonia and as far north as Alaska, including the Aleutian Islands. The flyway is bounded by the Pacific Ocean to the west and the Rocky Mountains to the east.

Some Rufous Hummingbirds use this flyway to make 3,000-mile journeys between Mexico and British Columbia. Several songbirds that winter in Central America and breed in Canada and beyond also use this flyway, including the Western Tanager and Townsend's Warbler. Shorebirds that use this flyway, like the Black-necked Stilt, will flock in huge numbers to stopover points like the Great Salt Lake in Salt Lake City, Utah, and Grays Harbor National Wildlife Refuge in Washington.

Other migration hotspots of the Pacific Flyway include Malheur National Wildlife Refuge in Oregon, and the following three places in California: Gray Lodge Wildlife Area; Don Edwards San Francisco Bay National Wildlife Refuge; and Monterey Bay (for seabirds).

Flyway Rule-breakers

Now that we've covered the major flyways and some of the birds that follow them, it's time to mention some of the birds that head to flyways less traveled. Many bird species take different routes in the spring and fall, but some take this to the extreme.

In the fall, some Blackpoll Warblers make an epic journey of more than 10,000 miles from Alaska to the Amazon with barely any stops. This includes nearly 2,000 nonstop miles over the Atlantic Ocean — an impressive feat for a bird that weighs less than a House Mouse. In the spring, though, Blackpoll Warblers plot an inland course instead, largely following the Mississippi Flyway.

Not to be outdone, the American Golden-Plover follows an even more circular migration path. Each year, it flies up to 20,000 miles as it journeys between its breeding grounds in the Arctic tundra and “wintering” grounds of southern South America (during the Southern Hemisphere's summer). The open-ocean leg of this trip, which traverses the eastern Atlantic and Caribbean, is longer than the coast-to-coast span of the U.S.

How ABC Helps Migratory Birds

Effectively conserving migratory bird habitat requires conservationists to think like birds. It's not enough to preserve and restore habitat in a bird's summer range: It's critical to ensure that birds have food-rich stopover points and ample wintering grounds as well.

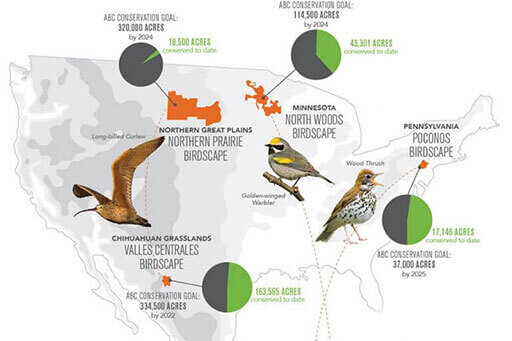

For example, warblers passing through Central Park could be impacted by forest loss in the Caribbean. Likewise, bright city lights in New York could endanger beloved winter birds in Central America. The Americas are connected by these flyways, which is why American Bird Conservancy protects migratory bird habitat through conservation zones called “BirdScapes.”

BirdScapes are strategically located in the most important places for migratory species. The Northern Prairie BirdScape, for instance, encompasses Long-billed Curlew breeding grounds along the Central Flyway, while shade-grown crops in the Guatemala Conservation Coast BirdScape provide winter habitat for Golden-winged Warblers that fly north along the Mississippi and Atlantic Flyways. To date, ABC has established nearly 100 BirdScapes across the Americas, with more on the way.

| Rachel Fritts is ABC's Writer/Editor. |