The steel-gray, red-capped Sandhill Crane is the most abundant of the world's cranes. Widely distributed throughout North America, this stately bird is one of only two North American endemic crane species. The other is the larger, much rarer Whooping Crane.

The steel-gray, red-capped Sandhill Crane is the most abundant of the world's cranes. Widely distributed throughout North America, this stately bird is one of only two North American endemic crane species. The other is the larger, much rarer Whooping Crane.

Habitat loss due to development and water diversion is the chief threat to Sandhill Cranes, especially in important staging and wintering areas such as Nebraska's Platte River. Collisions with wind turbines and communications towers also pose threats.

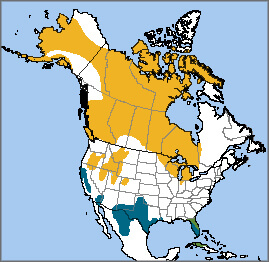

Six subspecies of Sandhill Crane are recognized, varying in size and weight. Three of these subspecies are migratory (Lesser, Greater, and Canadian) while three are non-migratory (Mississippi, Cuban, and Florida).

Scientists estimate that approximately 80 percent of all migratory Sandhill Cranes in North America use a 75-mile stretch of Nebraska's Platte River during spring migration; more than a half-million cranes “stage” in this area, preparing to continue the long journey north to breeding grounds in Canada and Alaska. During migration, they may fly as many as 400 miles in one day.

Dancing Duos

All cranes "dance” with one another, bowing, jumping, running, wing flapping, and tossing sticks or grass. Though most commonly associated with courtship, cranes of all ages may dance in any season. Crane dancing is thought to strengthen the bond between pairs and may also reduce aggression between birds.

Sandhill Cranes mate for life, pairing up as they migrate to breeding grounds in the spring. In a display known as "unison calling," mated pairs throw back their heads and point their beaks skyward, emitting a complex series of coordinated, rattling "kar-r-r-r- o-o-o" sounds. The Sandhill Crane female initiates the display.

Sign up for ABC's eNews to learn how you can help protect birds

Migrating en Masse

Sandhill Crane nests are usually a low mound of vegetation in a wetland, surrounded by shrubs or trees. The female typically lays two eggs, and incubation (by both sexes) lasts about one month. The male takes the primary role in defending the nest.

Chicks emerge covered in down, with eyes open and able to walk and even swim within eight hours of hatching. In the fall, juvenile Sandhill Cranes migrate south with their parents, remaining together for up to a year after hatching. The young birds reach sexual maturity in two years, although some may reach the age of seven before breeding.

Sandhill Crane and chicks by Jo Crebbin

During migration and winter, crane family units congregate with other families and nonbreeding birds, forming huge flocks that can number in the tens of thousands.

Like other cranes, Sandhills are omnivorous, using their long bills to glean and dig for a wide variety of plants, grains, small vertebrates such as mice and snakes, and invertebrates such as insects or worms.

Their appetite for grains sometimes leads to conflicts with farmers, as a large flock of cranes can quickly strip a field. In response, the International Crane Foundation is helping to develop a new technique to treat corn seeds with a deterrent before the seeds are planted.

Sandhill Success Story

The Sandhill Crane is one of the world's few crane species that is not currently threatened. Although most of the subspecies' populations are increasing, the Mississippi and Cuban birds are listed as endangered under the Endangered Species Act. The Mississippi population is also included on the State of the Birds Watch List.

For these and other rare species, the Endangered Species Act works to prevent extinctions—but the Act itself is now under threat. Learn more about threats to the ESA.

Donate to support ABC's conservation mission!