Martha: The Last of Her Kind

The old man's voice didn't shake or tremble. Despite his years, the words came over the telephone as strong and bold. “How old are you?” I asked.

“Well now, how old do I sound?” came the reply.

“You sound like you're in your 40s or 50s.”

“Just add on about 40 more years and you got it right.” There was a playful streak in Richard Fluke, a bit of the imp.

“Then how old were you when you first saw the bird?”

“My first trips to the zoo were around 1907. I was a little kid, in grade school, and I was out there every year because I loved animals.”

The original pagoda-style aviaries at the Cincinnati Zoo were built in 1875. Martha, the last living Passenger Pigeon, spent her final years in the largest pavilion, which still stands and is now a National Historic Landmark.

Fluke, born in 1896, would have been around 10 years old at the time, in the middle of that short stretch of years between the toddler stage and puberty when the mind first begins to comprehend the world in wonder. At that age, children are often fascinated by nature. This was true for Richard Fluke. “Every time I got a chance, why, I went to the zoo,” he said. “I loved it.”

“That's where you saw Martha?”

“Right.”

“Were you aware then that Passenger Pigeons were almost extinct?”

“Yes, because they had a sign there, of $1,000 that they'd give if you could find a mate for her. Everybody that went through there, that sign was up on the front, [explaining that] if somebody had one, a male especially, they would give $1,000 for it, for a mate for her,” he said. “She was the last that was known.”

‘She Had No Fear'

At the time I talked to him in the 1980s, Richard Fluke was believed to be the last person still living who remembered seeing the last living Passenger Pigeon, Martha. He was a one-time opera singer; a former manager of a piano store in Cincinnati, Ohio; and lifetime patron of the zoo where his friend Martha lived and died.

“I used to go out on Saturday afternoons in summertime,” I hear his tape-recorded voice telling me, decades after our interview. “I was out there, oh, a couple of times a week. I'd spend 10 cents on a streetcar to take me. It was five cents out and five cents back.” He chuckled to himself, recalling the prices. It was a long time ago.

“Martha was a great bird. She was very docile. She was easy to handle. If you were with her very much and talked to her in the right kind of language, soft and easy, she got to know you.”

“Did you get to handle her?” I asked.

“Oh yes, sure.”

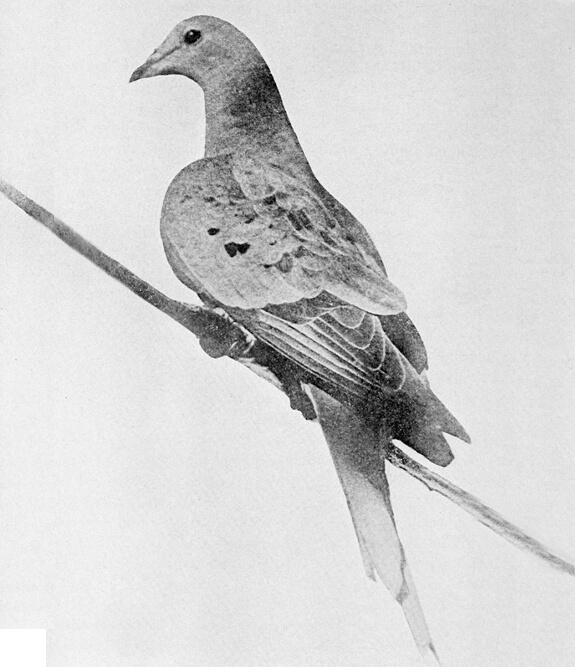

Martha the Passenger Pigeon (pictured in life) died at the Cincinnati Zoo on September 1, 1914.

“You were allowed to pick her up?”

“Yes. I had open sesame at the zoo when I'd go, because they knew I loved animals and could handle them.”

“Did the keeper let you feed Martha?”

“I used to feed her peanuts. I'd give her little things and she would take them.”

“She'd take a peanut from your hand?”

“When I'd break it up real small, yes. I didn't feed her too often, but now and then I'd do it, as kids will. And I got to the point where I could talk to her. She had no fear. There were some other pigeons in with her for company.”

“They had regular, domestic pigeons in there?”

“They had a couple in there for her, so she wouldn't be lonely.”

Martha's Final Flight

Near the end, when the great wild flocks that had numbered in the billions had vanished, when only tiny groups could be found, scattered here and there, individual pigeons were sometimes seen in the company of other avian species: a single Passenger Pigeon perched near a pair of Mourning Doves, or a pair of pigeons flying near a loft full of European Rock Doves.

In captivity, their numbers had dwindled as inexorably as in the wild, where market hunters netted them, shot them or knocked them out of the trees with long poles, afterward shipping them in boxcars to restaurants in the cities. The few captive breeding pairs failed to produce viable eggs. Gradually, one by one, the remaining birds succumbed to the ravages of age.

Large flocks of Passenger Pigeons once darkened the skies, but by the late 19th century, unchecked hunting pushed the species to the brink of extinction.

The aviary where Martha was kept, built in 1875, is today a National Historic Landmark. Constructed in the style of a Japanese pagoda, it has bright canary-yellow walls, and its orange roof tiles, tilting upward at the edges, look like ski-jump runways, ready to launch flights into the sky.

Martha made her last flight in 1914. On September 1, her lifeless body was found on the ground in the aviary.

“The world lost a great bird,” said Fluke, his voice still emotional at the memory, even after 74 years. “She was just magnificent. When [she died], I felt that I had lost a pal, because I always went around to see her.”

Perhaps this is the greatest value of Richard Fluke's testimony. Others mourned Martha's loss — and still mourn it — in the abstract, as the point final in the tragic history of a species wasted through human greed. But the little boy who sat in the yellow pagoda, talking to her, stroking her feathers, feeding her tiny bits of food, mourned the passing of his friend.

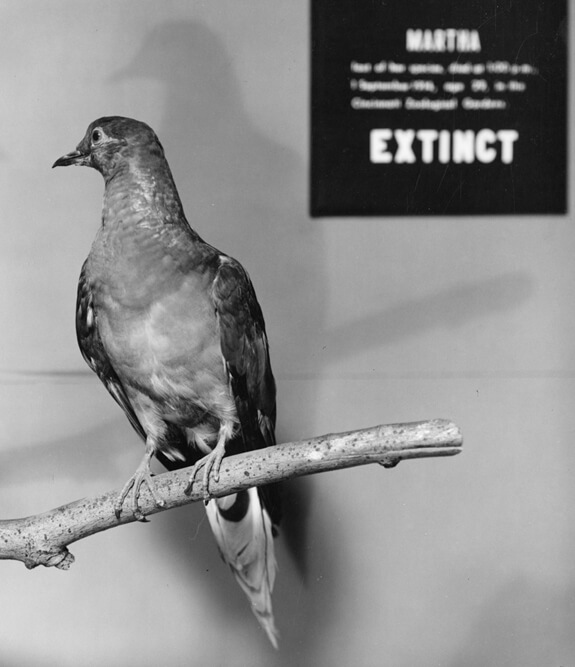

The stuffed specimen of Martha the Passenger Pigeon now resides at the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, DC.

It must have marked him, because for the rest of his long life he paid a special attention to wildlife, and after his youthful wandering and his singing career, when he came back to Cincinnati and settled down, he resumed his trips to the zoo.

“You felt pretty badly then, when she died?”

“I surely did. I feel badly right till recently,” he says on the tape.

He was the moving spirit behind the decision by a local animal conservation group to preserve the little yellow pagoda, and erect a monument there to his boyhood friend. The group of two dozen or so people contributed more than $100,000. Other donors chipped in, and in 1977, the restored former birdhouse became a center for an education program in the protection of endangered species.

For the rest of his life, Fluke was a fervent supporter of the zoo, and a friend to its animal inhabitants.

A Little Boy and a Small Bird

I talked to Richard Fluke in 1983, intending to write about it then, but never did so. I wasn't sure why, until now.

He died in 1988, at 92. His obituary in the Cincinnati Enquirer made no mention of Martha.

But on the tape, it is clear from the sound of Fluke's voice that one of the most meaningful encounters in his life may have been with the tiny bird he met in the yellow pagoda at the zoo. Fluke's encounter provided a lesson about the relationship between humans and the natural world of which we are an integral part.

Passenger Pigeons by Louis Agassiz Fuertes/Public domain

Long ago, in 1907, this little boy found a friend in a small bird, the last of her kind, and lost that friend a few short years later. There would never be another Martha.

The decades passed. But Martha's memory lingered, along with the finality of extinction. In 1977, more than 60 years after her death, when he assisted at the dedication of the zoo's renovated aviary, Richard Fluke stopped in the middle of his remarks — to cry.

Editor's note: This story is a little different from most of the features we publish on this blog. How did Thomas Pawlick decide to write about Richard Fluke? And why did so much time pass between the initial interview and the publication of this story?

"I phoned him and interviewed him and wrote up a story," Pawlick says. "Then the magazine I worked for, and which had wanted to use the story, changed hands. I left, with the still-unpublished story, and immediately became preoccupied with finding another job. That was back in the 1980s. I forgot the story and only saw it again this year, in an old file. With the upsurge recently in species extinctions, and the prospect of a lot more with climate change, it seemed as timely as ever."

We at American Bird Conservancy are honored to publish this moving account of a lost species and the people who cared.

| Thomas Pawlick is a retired university professor of science journalism. He has published 10 books and has won numerous national and international awards for his writing. He lives on a farm in eastern Ontario, Canada. |