Six Extinct Birds Whose Fame Lives On: The Dodo, Passenger Pigeon, and More

More than 180 bird species (out of around 10,000 total) have likely gone extinct over the last 500 years, and the rate of extinction is accelerating.

Bird species have disappeared for a number of reasons. These include: competition with and predation by introduced species, unsustainable hunting and trapping by humans, habitat loss due to human activities such as agriculture and logging, and a combination of these factors.

Today, the birds most at risk of extinction tend to be those reliant upon specific, niche environmental conditions. Many of these occur within small, restricted ranges. This suggests a future of declining biodiversity that favors widespread, generalist species.

A species' disappearance can have rippling ecological, cultural, and even economic effects, and as we enter what many experts consider our planet's sixth mass extinction, we should all be alarmed about what the future may hold.

But the news isn't all bad: In recent decades, spurred by the permanent loss of the species listed below and others, there have been successful conservation actions that have prevented other losses.

Our List of Extinct Birds

The list below introduces you to some of the most famous birds to have gone extinct around the world. They represent a broad range of bird families, and their extinctions happened in time periods stretching from the Renaissance to just a few decades ago.

Although you'll never add any of these birds to your life list, we hope they'll serve as a reminder of what we've lost, and as motivation to continue to support critical conservation efforts for the endangered birds still with us. Keep scrolling below the list to learn how conservationists are fighting against extinction and how you can help imperiled birds bounce back.

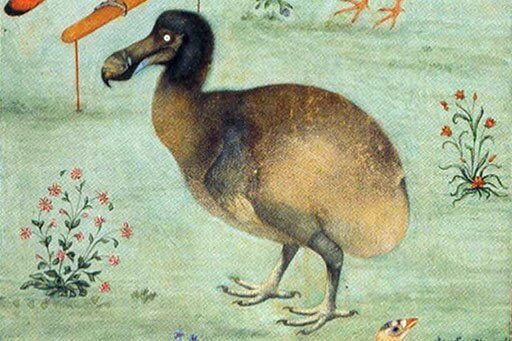

Dodo

Perhaps the most famous extinct bird, this near-mythical animal was found only on Mauritius, a small island east of Madagascar in the Indian Ocean. First mentioned in the journal of a Dutch naval officer who visited the island in 1598, Dodos were toddler-sized flightless pigeons that had no natural mammalian predators and therefore no fear of humans. A combination of hunting for food by settlers, egg predation by introduced animals such as pigs, and the destruction of their forest habitat led to a rapid decline in their numbers after Dutch colonization. The last reliable Dodo sighting was in 1662. The species likely went extinct by around 1690. Modern reconstructions suggest that the Dodo was fast, agile, and had an excellent sense of smell that helped it locate ripe fruit.

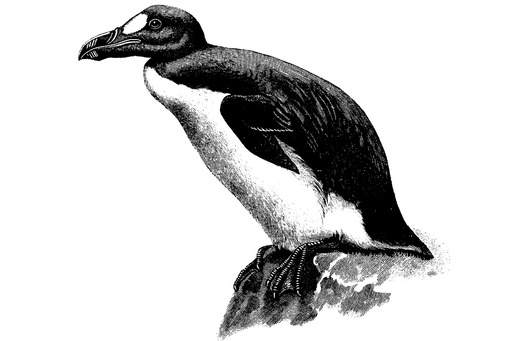

Great Auk

The word “penguin” was originally coined not to describe the flightless birds of the Southern Hemisphere, but rather this large, flightless relative of murres and puffins (which can fly). Standing over two feet tall, the Great Auk bred in large colonies along the northwestern Atlantic coast; the last known breeding colony was on an island east of Newfoundland. This species probably lost the ability to fly as an adaptation to improve diving abilities so it could pursue larger fish. Unfortunately, flightlessness also made this bird an easy target for hunters. Ill-fated attempts to legally protect the Great Auk began in the 1790s, when British colonists in Newfoundland noticed the bird was becoming much less common. The last two known adults were killed near Iceland in 1844.

Labrador Duck

Relatives of eiders, Labrador Ducks were last seen in 1875. Although they likely bred in remote areas along the eastern coast of Canada, no nests were ever documented, and much about this species remains a mystery. Labrador Ducks had odd bills that widened and flattened toward the end and were full of comb-like structures called lamellae. Some experts believe that this odd bill hints that the species had a specialized diet, and that perhaps these ducks foraged for shellfish and crustaceans in soft mud and sand in shallow water. Labrador Ducks were already rare before the arrival of Europeans, and we may never know to what degree hunting and egg-harvesting contributed to their extinction.

Passenger Pigeon

Enormous nomadic flocks of Passenger Pigeons numbering in the hundreds of millions, perhaps even billions, once roamed the eastern U.S., following bumper crops of beechnuts and acorns across the deciduous forest landscape. Nineteenth-century naturalists famously described the flocks as darkening the sky for days at a time. But as railroads penetrated further into the core of the Passenger Pigeon's range, these birds were slaughtered in huge numbers at nesting colonies, their carcasses shipped to large cities as food. Combined with habitat destruction, this eventually caused this species' numbers to decline to a point from which recovery was impossible. The Passenger Pigeon was likely extinct in the wild by the beginning of the 20th century. Martha, the last of her species, died in captivity at the Cincinnati Zoo in 1914.

Carolina Parakeet

It may be hard to believe today, but a native parrot species also once ranged across much of the eastern United States. Brightly patterned in green, yellow, and orange, Carolina Parakeets streamed across the countryside in large, noisy flocks, munching on seeds of cocklebur, thistle, and other plants, as well as a variety of fruits. Once common, they became scarce by the middle of the 19th century, and the last known bird died in 1918. Why the last Carolina Parakeet population in Florida vanished is still debated, but persecution by farmers who saw them as crop pests, the market for decorative feathers, habitat loss, and even disease may all have played a role.

Po‘ouli

In September 2021, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service announced that the Po‘ouli, a Hawaiian honeycreeper and the only member of the genus Melamprosops, was extinct. Found only on Maui, the Po‘ouli subsisted on a diet of insects, snails, and spiders. When discovered in 1975, this species' population was already in accelerated decline, and final efforts to breed the last remaining birds were ultimately unsuccessful. The last verified sighting came in 2004. As is the case with other endangered and extinct Hawaiian forest birds, the most important factor in the birds' decline was probably avian malaria carried by introduced mosquitoes.

How Conservationists Prevent Bird Extinctions

In the Americas and U.S. Pacific Territories, 20 bird species have gone extinct in the wild since 1968. In 2021, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service proposed taking 11 bird species off of the Endangered Species list due to extinction — eight from Hawai‘i alone.

Many more species face the same danger: 263 bird species in the Americas and U.S. Pacific Territories are listed as Endangered or Critically Endangered on the IUCN Red List — the organization's two highest threat levels.

The good news is that decisive action can help many bird species recover: Scientists estimate that 17 bird extinctions in the Americas have been averted by conservation intervention since 1994.

American Bird Conservancy and conservation partners have been involved in protecting a number of these species, and we are leading the charge to protect at-risk populations and prevent bird extinctions across the Americas.

In Hawai‘i, we support innovative solutions to fight threats such as invasive mosquitoes, which carry avian malaria. Several endemic honeycreepers have already vanished since the introduction of this deadly disease in the 1940s, including the ‘Akialoa and Po‘ouli (above). Without bold conservation intervention, avian malaria will likely drive four more species extinct within the next decade. Several other Hawaiian forest birds are nearly as endangered and require urgent conservation action to prevent their extinction.

In Latin America and the Caribbean, we have helped establish a network of more than 100 reserves to protect habitat for dozens of the rarest bird species, including hummingbirds such as the Marvelous Spatuletail in Peru, the Short-crested Coquette in Mexico, and the Blue-throated Hillstar in Ecuador.

In coastal waters and beyond, we work to restore populations of Critically Endangered seabirds such as the Waved Albatross. To do this, we promote sustainable fisheries and protect nesting colonies from predators such as invasive cats, through actions that include installation of predator-proof fencing.

Help Stop Bird Extinctions

One of the easiest ways to get involved is to support ABC's bird conservation work. In July 2022, we launched the Preventing Bird Extinctions Fund to help save rare and endangered bird species. Donations to the fund support ABC's work in Hawai'i, Latin America, and the Caribbean, as well as in ocean waters.

| Rebecca Heisman is a science writer based in eastern Washington. Her first book, which tells the scientific backstory of how we know what we know about bird migration, will be out in spring 2022. |