American Bird Conservancy Leads Expansion of Tagging Network For Migratory Birds

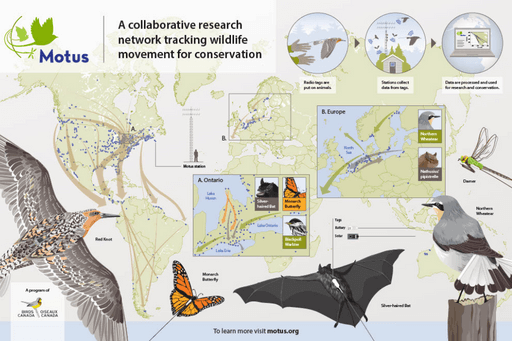

Not long ago, scientists couldn't seriously consider tracking a bird smaller than a Mourning Dove through its migration. The typical tags were just too big and bulky. In the last decade, however, a new research network called the Motus Wildlife Tracking System — consisting of tiny “nanotags” and a collection of stations built specifically to pick up their signals — has revolutionized migratory bird tracking in North America. This, in turn, is giving conservationists unprecedented insights into the habitat they need to protect and restore to help save struggling migratory bird populations.

Since Motus stations first began to go up less than a decade ago, hundreds of them have been placed on the landscape to collect data on the movements of migratory species. But there are still vast areas along major migratory flyways that lack coverage that could provide key information to manage and conserve Vulnerable and Endangered migratory species. To facilitate the placement of new stations to target these bird species, American Bird Conservancy (ABC), in partnership with Birds Canada, has hired a new Motus Director for the United States. Two regional coordinators for the Southeast and Northwest U.S. will soon join him.

What is Motus and Why is it Useful for Bird Research and Conservation?

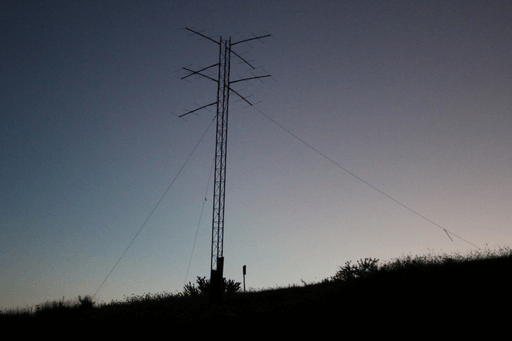

Motus (Latin for “movement”) is a wildlife tracking network using automated radio telemetry. It was launched in 2014, soon became a program of Birds Canada, and has rapidly spread with the help of hundreds of collaborators. To date, more than 1,500 Motus receiver stations have been installed across 34 countries, though most towers are still concentrated in the U.S. and Canada, where the network began.

The Motus network has spread so quickly because it bundles a few key elements that make it broadly useful for researchers and conservationists. One of these benefits is the miniscule size of the radio tags used. They can weigh as little as one-tenth of a gram, the weight of a single pine nut. There aren't many other tagging options that are lightweight enough to fit on a warbler — or even a dragonfly — while transmitting data to enable real-time tracking.

Geolocators and GPS loggers, for instance, are lightweight but only store data. They can't transmit it. That means scientists have to recapture tagged birds to get information, which only happens in a small fraction of cases. Satellite tags, conversely, can transmit data but are too large to put on anything smaller than a meadowlark. While satellite tags continue to get lighter as technologies improve, the smallest varieties are still at least 30 times heavier than the smallest Motus tags.

“Motus's sweet spot is tracking small animals — especially migratory birds — over large distances,” said Adam Smith, ABC's new Motus U.S. Director.

Another major benefit of Motus is that the barrier to entry is low. Once an individual or organization acquires the appropriate state and federal permits, they simply need to purchase the radio transmitters that emit the right frequency and affix them on their study subjects. Then, biologists can just sit back and wait for existing towers to “hear” the pings sent out from their bird's transmitter, which the receivers can pick up from up to 10 miles away. The data collected is then not only available to the researchers, but shared on motus.org for anyone to use.

Finally, placing new receiving stations is also relatively straightforward. Pretty much anyone can put up a receiver station if they have suitable funding and a site with good, clear line of sight for the radio antennas. There are Motus stations on wildlife refuges, zoo grounds, and even private ranches, to name a few locations.

However, because the network is still expanding, there are many gaps in Motus receiver coverage. In order to best use Motus's capabilities to understand when and how birds use certain habitats, key gaps in the network must be filled. That's why there are plans in the works to strategically build out the network along key bird migration paths.

How is Motus Spreading, and What is ABC's Role?

The Motus network began with a collection of receivers in the southeast of Canada and the northeast U.S., and soon expanded around the Great Lakes region. “It has spread naturally and quickly from there,” Smith said. “People are starting to recognize the potential of it.”

However, there are still some big, key areas without receivers in the western and southeastern U.S., and Central and South America have very sparse coverage as well. Part of the reason for this is logistical. Some places are more challenging to get to, or aren't as suited to putting up a station. But another reason is that the network has grown organically, without a clear unifying goal.

“People see Motus in the news, and they want to get involved, and you have this spontaneous organic growth, which is great,” Smith said. “But it's also challenging, because you have a lot of different groups doing their own thing, not always in parallel, and traveling the Motus learning curve over and over again, which is not necessarily efficient.”

Smith's role was created, in part, to help all of these different groups collaborate more deliberately and find commonalities in their goals. Smith will work closely with two new ABC-employed regional coordinators and other external regional coordinators across the country to help with the outreach and collaboration necessary to help Motus grow more strategically and efficiently over the coming years.

“It benefits everybody if we can make it simpler to participate,” Smith said.

ABC is uniquely well-suited to host the U.S. Motus Director role and help expand the network, according to Smith, because the organization already does conservation work across migratory birds' full annual life cycles. ABC works with partners to conserve bird habitat in Central America, the Caribbean, and South America, where Motus stations are still scarce.

The organization has already helped install a Motus station in Nicaragua's El Jaguar Reserve to track Louisiana Waterthrushes and Wood Thrushes. Researchers found that some of the Wood Thrushes that winter in El Jaguar breed in the Appalachian Mountains, where the ABC-led Appalachian Mountain Joint Venture operates.

“That is a tremendous asset that I'm looking forward to leveraging,” Smith said. “To be able to come to ABC and work on Motus and migratory birds and their conservation full-time is really exciting to me.”

###

American Bird Conservancy is a nonprofit organization dedicated to conserving wild birds and their habitats throughout the Americas. With an emphasis on achieving results and working in partnership, we take on the greatest problems facing birds today, innovating and building on rapid advancements in science to halt extinctions, protect habitats, eliminate threats, and build capacity for bird conservation. Find us on abcbirds.org, Facebook, Instagram, and Twitter (@ABCbirds).

Media Contact

Jordan Rutter

Director of Communications

media@abcbirds.org