Prairie Plight: Five of the Fastest Declining Grassland Birds in the U.S.

Native grasslands sequester carbon, build and conserve soil, and support important bird communities — and yet they've been called one of the world's “most endangered ecosystems.” According to some estimates, around 360 million acres of North America's original native prairies have already been lost through conversion to croplands, degradation from over-grazing, and the encroachment of woody plants due to fire suppression. Another 125 million acres are at high risk.

Not surprisingly, the birds that rely on this habitat are in trouble. A major study co-authored and supported by American Bird Conservancy (ABC) found that there are 3 billion fewer birds in the United States and Canada today than there were in 1970. Grassland birds as a group have been hit especially hard, with a 53-percent reduction in their overall population — the greatest bird decline in any single terrestrial biome. In total, three-quarters of the bird species that depend on grasslands have seen significant drops in their numbers.

But there's still reason for hope, and conservation groups including ABC are working to reverse these losses. A good part of this work is done in partnership with landowners on working lands, and with organizations and agencies on both sides of the border with the U.S. and Mexico. Here, we introduce you to five of the fastest-declining North American grassland bird species — and how you can help save them.

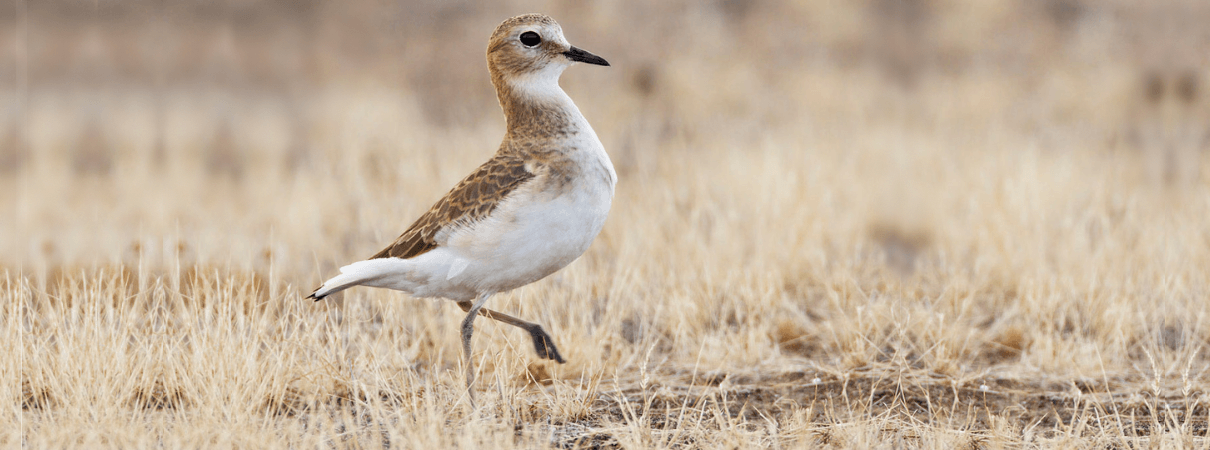

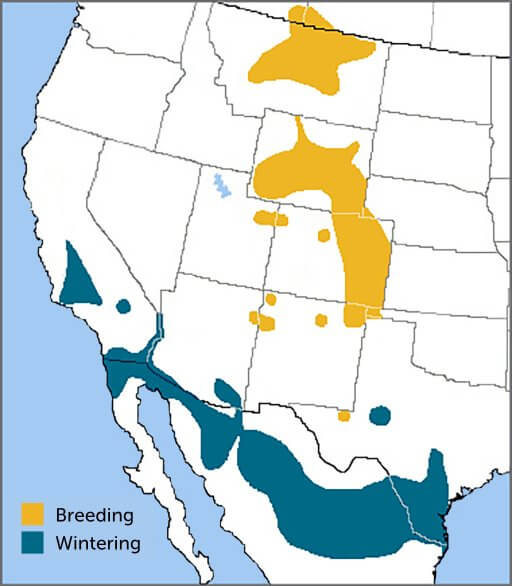

Mountain Plover

Although part of a family strongly associated with coastal areas, Mountain Plovers live far from the water. They breed in dry areas of the western Great Plains, where they share space with pronghorns, bison, and prairie dogs that help maintain the sparsely vegetated habitat they rely on. In winter, they migrate to California, other southern border states, and northern Mexico; in some areas, they form large flocks. With their drab, pale brown plumage, Mountain Plovers seem to vanish into the grass when they freeze in response to a threat, earning them the nickname “Prairie Ghost.” These grassland birds have declined by 71 percent since 1970, and have been proposed for protection under the Endangered Species Act multiple times. The main threat to Mountain Plovers is habitat loss due to the expansion of intensive crop agriculture and the loss of bison and other key native herbivores. Pesticides and oil and gas development may also be factors.

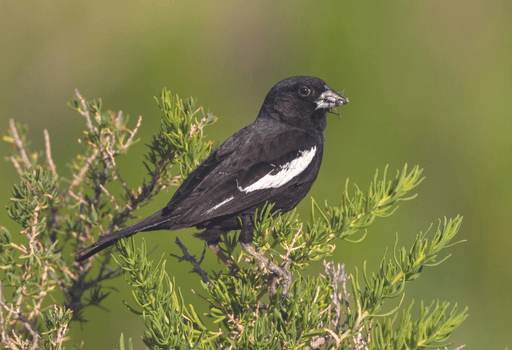

Lark Bunting

The bold black-and-white plumage of breeding male Lark Buntings sets these members of the sparrow family apart from most other grassland songbirds. They breed in grassland and shrub steppe habitat in the high plains of central North America and winter in parts of Texas, New Mexico, and Arizona, as well as in Mexico. Lark Buntings are also notable for their elaborate flight displays: Males woo females by launching themselves 20 to 30 feet into the air, then drifting back down on outstretched wings while singing a complex “flight song” of whistles and trills. Lark Bunting populations can vary dramatically from place to place and year to year in response to factors like drought, but overall their populations have dropped by 72 percent since 1970. Like other grassland birds, their decline is closely linked to habitat loss, but that is not the only threat these disappearing birds face: Grasshoppers, which they capture in the air and on the ground, are a key part of their diet, and shrinking insect populations due to pesticide use may be partly responsible for the Lark Bunting's decline.

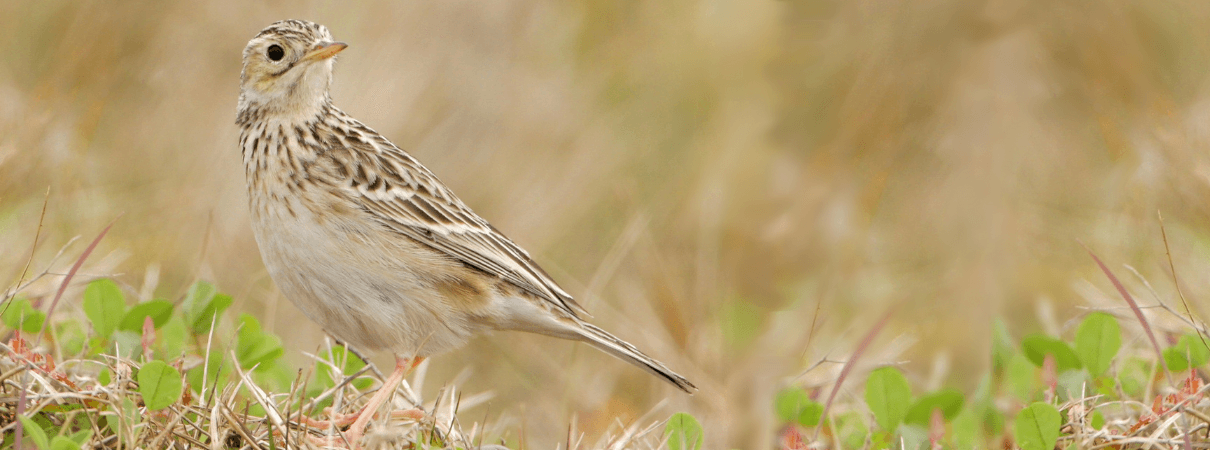

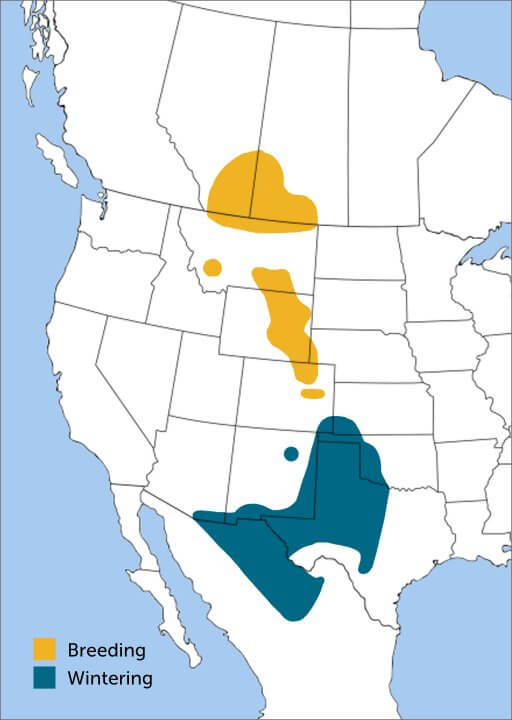

Sprague's Pipit

Sprague's Pipits are slender, long-legged, and long-tailed birds. They have what may be the longest aerial display of any species: Males have been known to continue their displays for up to three hours at a time, circling high above the ground while singing a handsome song consisting of a descending cascade of bell-like notes. The rest of the time, however, these birds can be hard to spot. As is the case with many grassland songbirds, they have pale brown plumage that helps them blend in and they build inconspicuous nests concealed in grasses. Sprague's Pipits breed in mixed-grass prairies along the border of the U.S. and Canada and migrate to the south-central U.S. and northern Mexico for the winter months. These birds are particularly sensitive to human disturbance, and their numbers have dropped by 74 percent since 1970, due largely, again, to habitat loss.

Thick-billed Longspur

Another grassland songbird, another beautiful aerial display. In the case of Thick-billed Longspurs, this includes showing off their boldly patterned black-and-white tails and singing a tinkling song as they descend. They breed in native shortgrass prairie along the U.S.-Canada border, and in some cases, they benefit from grazing, which can create the sort of short, sparse vegetation they prefer. In fall, they head south to spend the winter in southern plains states and northern Mexico. Habitat destruction caused by tilling and pesticide use have had significant negative impacts on Thick-billed Longspur populations, and they've declined by 82 percent since 1970. Thick-billed Longspurs used to be known as McCown's Longspurs, after John P. McCown, a Confederate general who supported slavery and persecuted American Indians. In 2020, the species' common name was changed to eliminate the reference.

Chestnut-collared Longspur

The Chestnut-collared Longspur is the smallest of the four longspur species, which are named for long claws on their hind toes that are believed to help them walk on uneven ground. Like related Thick-billed Longspurs, Chestnut-collared Longspurs breed along the U.S.-Canada border and migrate to parts of Texas and surrounding states, and northern Mexico, but they prefer mixed-grass prairie, especially in areas grazed by bison or disturbed by fire. Males in breeding plumage are especially striking, with black-and-white faces and the chestnut napes that give them their name. The more inconspicuous females incubate their eggs on well-hidden nests while males stand guard, and both parents team up to drive away predators such as harriers and shrikes. Habitat loss and fragmentation due to agriculture and development, plus other factors such as fire suppression, have caused this species' numbers to plummet by a staggering 84 percent since 1970.

Grassland Bird Conservation

ABC is helping grassland birds bounce back by working with our regional Migratory Bird Joint Venture partners and hundreds of private landowners. In recent years, we have enhanced management on more than 100,000 grassland acres from North Dakota to Mexico, using safely applied prescribed fire and grazing to mimic natural ecosystem processes. By promoting best management practices on private working lands, where most of these habitats occur, we are improving the prospects for declining grassland bird species. ABC also promotes bird-friendly measures to be included in the Farm Bill.

How You Can Help Grassland Birds

Policies enacted by the U.S. Congress and federal agencies, such as the Natural Resources Conservation Service and U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, have a huge impact on America's birds, including grassland birds. You can help shape these rules for the better by urging lawmakers to prioritize birds, bird habitat, and bird-friendly measures. To get started, visit ABC's Action Center.

Although grassland birds play a critical role in the ecosystems they inhabit, they tend to be overlooked, especially when compared with other bird species. You can learn more about these fascinating birds and the threats they face by signing up for ABC's Bird of the Week email series.

American Bird Conservancy and our Migratory Bird Joint Venture partners have improved conservation management on more than 8.5 million acres of U.S. bird habitat — an area larger than the state of Maryland — over the last ten years. This is a monumental undertaking, requiring the support of many, and you can help by making a gift today.