Don't Let the Sun Set on Evening Grosbeaks: Take Action Against Collisions at Home!

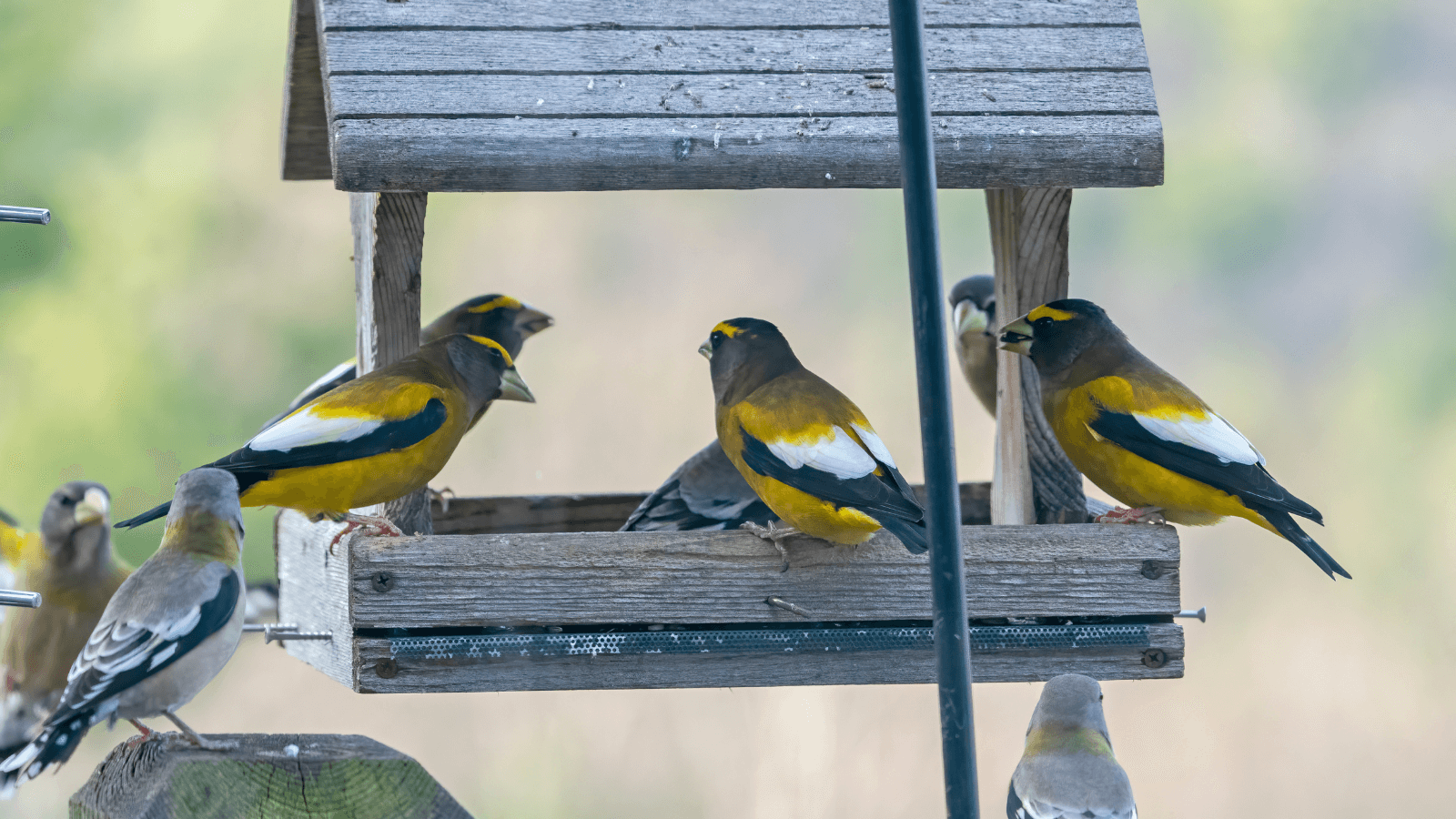

Sandy had been waiting for her snowy yard to be filled with bright yellow and black colors, reminding her of sunflowers, like the recent local photos she'd seen on Facebook. Every morning she filled her bird feeders with the recommended seed mix, waited, wondered, and watched. One cold morning in late December, as she refilled her tea, her eyes caught a flash of yellow flying past her picture window. She hurried to peer outside. They had arrived! Hundreds of Evening Grosbeaks filled her cedar tree, shrubs, and bird feeders! The smooth transitions from yellow bodies to black and white wings gave them the appearance of wax carvings. Their large, seed-crushing, ivory-colored bills contrasted with their dark heads and yellow eyebrows. She held her breath so she could hear their cheerful, blurry chirps through her windows. They had finally arrived and brightened the short winter days!

Evening Grosbeaks have long been a delightful presence, bringing joy to the lives of birders and people who feed birds. But sightings are increasingly less common, and flocks are getting smaller. Over the last 50 years, within Sandy's lifetime, Evening Grosbeak populations have decreased by more than 90 percent. Scientists are still working to understand the reasons why.

Researchers from the Bird Banding Laboratory (the Lab) may help answer questions about bird species with declining populations, including Evening Grosbeaks. The Lab is a science program that was started in 1920 to help track and share the numbers of birds banded and where those bird bands are rediscovered. The Lab has 100 years of bird band data showing that, in some decades, Evening Grosbeaks were the most commonly found banded birds after they had apparently collided with windows.

On April 4, 2022, David Yeany, an avian ecologist with the Pennsylvania Natural Heritage Program, banded Evening Grosbeak number 228 and 17 flock mates in Aroostook County, Maine. As part of a larger project focused on conserving Evening Grosbeaks, David also attached a radio tag to 228. Almost two months later, 228's radio tag was heard near Cap Gaspe, Quebec, which is about 240 miles northeast of where he was banded in April. David believes 228 may have spent his last nesting season near Cap Gaspe. Six months later and 920 miles away in Grand Bend, Ontario, 228 was killed when he collided with a window. Evening Grosbeak 228 was around a year and a half old.

How many years would 228 have lived if the window had been marked with a bird safe design? Evening Grosbeaks have been known to live for over 16 years! But there are more questions we can't answer. How many of 228's flock mates hit windows? How many young birds would 228 have helped raise if he hadn't died in this collision? How many more miles would 228 have traveled? How many people would have enjoyed his visit to their bird feeders? We will never know.

There is an urgent need for action so that birds like 228, and all species of birds, have a better chance of survival. It is still not clear why birds collide with windows, but we do know birds don't see clear glass and seem to collide with windows when they fly towards natural reflections of habitat, like sky or plants. Collisions also happen more when they fly towards lights shining through windows or from nearby porches and yards. Although some birds may seem fine after a collision with glass, most die later from head or other injuries.

The Solution

As many as one billion birds collide with glass every year in the United States. Fortunately, there are simple ways to help fix this piece of the Evening Grosbeak puzzle by making our windows visible to birds! As we enjoy filling our winter yards with bright colors and songs, we need to take simple steps to help these beautiful birds. Prevention is the best option.

There are many inexpensive and attractive options for making windows visible to birds. Simply hanging a few hawk silhouettes or decals is NOT enough. Window patterns should include at least a two-inch by two-inch grid on the outside of windows, even if the dots are small. For low-cost, temporary methods: make and hang a paracord bird curtain or create decorative patterns using tempera paint and stencils. For more long-term solutions: apply decal markers (dots), external screens, or use fritted glass.

Now is the time to find a solution that matches your budget and style to treat your windows for immediate bird protection. This simple act can go a long way in protecting birds. Commit to treating your windows before filling your feeder again, share your efforts with family and friends and on social media (#3billionbirds #birdcollisions #eveninggrosbeak), and ask bird seed retailers to carry glass treatment options with a 2-inch by 2-inch pattern applied to the outside of the window.

Together we can help these beautiful birds that bring the colors of sunshine and sunflowers to short winter days!

This article was originally published on the U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service website and reprinted with permission.