Common Backyard Birds of the United States

If you're just getting interested in birds, identifying the ones that live in your backyard or neighborhood is a great place to begin. With a little guidance and patience, most people can quickly learn to recognize these common birds by sight and sound.

To get started, take a look at the illustrated list below, which includes 10 of the most common backyard birds found nationwide. Further down, you'll find two additional lists with backyard birds specific to the eastern and western U.S. These useful lists will help you zero in on more common birds in your region.

We've also included important information about threats to backyard birds — yes, even some of these “common” birds are in decline — and how you can help. And at the bottom of this post, you will find helpful tips on identifying backyard birds, links to useful resources, and essential considerations to keep in mind when feeding birds.

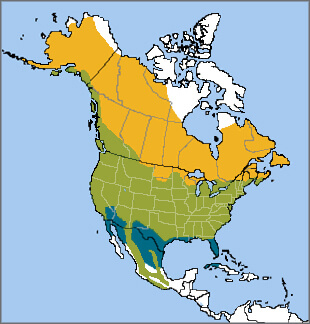

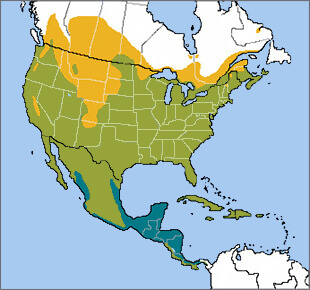

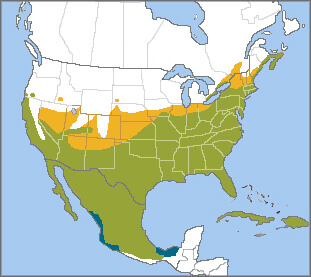

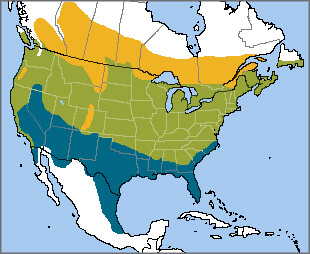

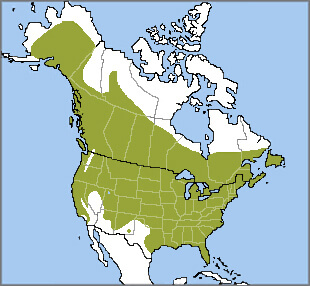

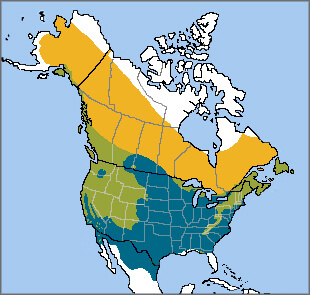

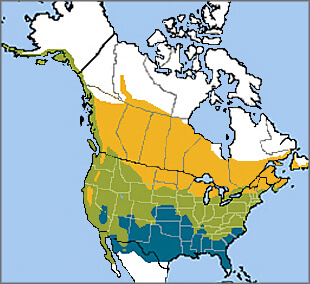

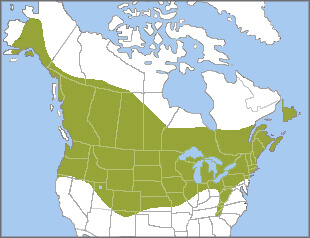

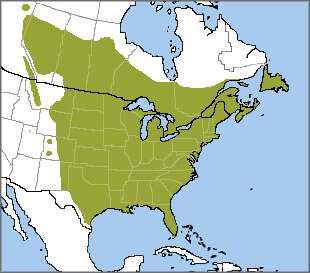

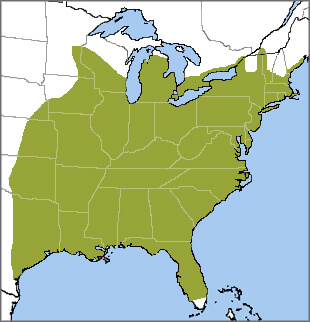

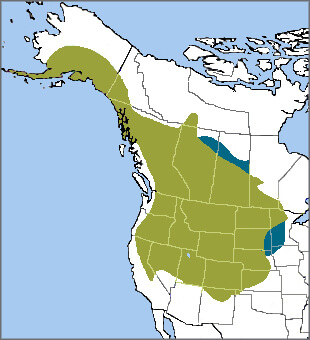

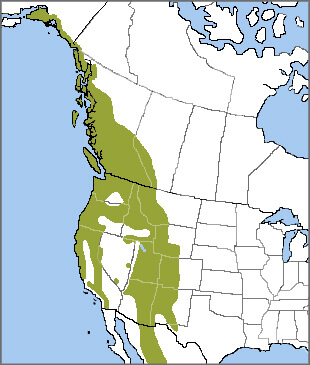

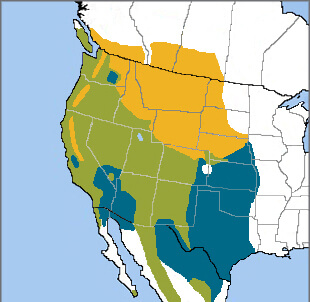

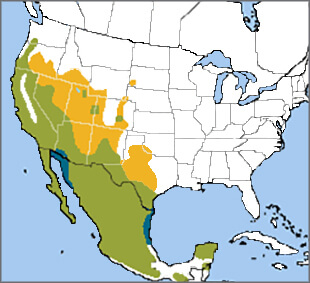

A note on our maps: Orange areas represents breeding range; teal represents winter range; and green represents year-round resident areas. Finally, although non-native species such as European Starlings and House Sparrows are readily found in backyards, we've opted to focus exclusively on native species.

Backyard Birds Found Across the U.S.

American Robin

Found throughout North America, this familiar orange-breasted thrush may be the most abundant bird in the U.S. and Canada. Though many think of robins as a sign of spring, you may be just as likely to see their wandering flocks in fall and winter, when these versatile birds switch from worm-hunting on lawns to seeking berries in trees and shrubs. Listen for their “cheerily, cheer up, cheerily, cheer up” song from before dawn to evening from early spring well into summer.

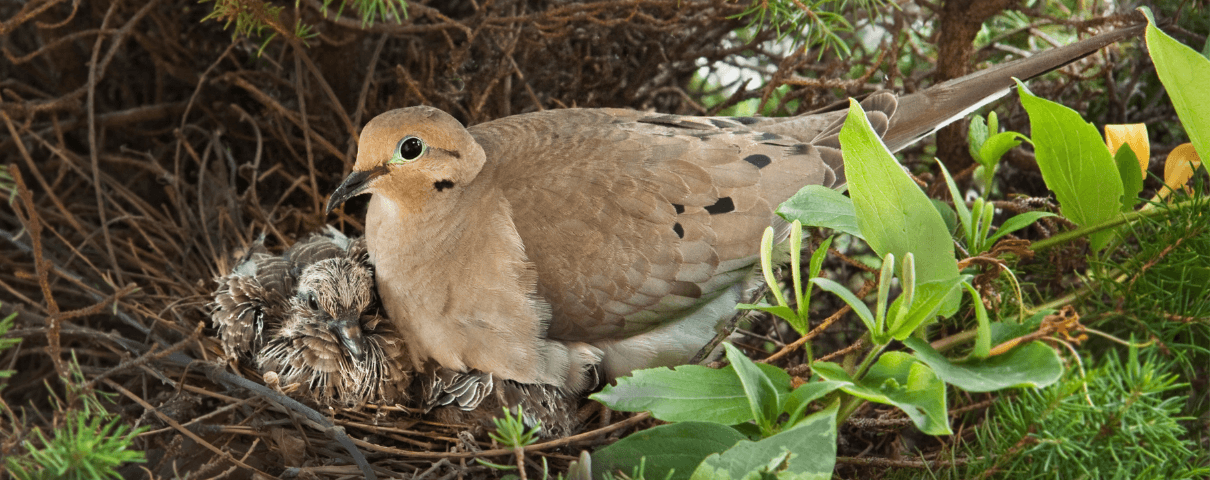

Mourning Dove

The Mourning Dove's name comes from its melancholy-sounding coos, which the casual listener might mistake for the calls of an owl. (Also keep an ear out for the whistling sound their wings make as they take off!) Mourning Doves inhabit a wide range of open habitats, including suburbs and urban parks. Although targeted by many predators, Mourning Doves remain plentiful thanks in part to the ability to nest a number of times each breeding season. One way that you can distinguish this species from its larger non-native cousin the Eurasian Collared-Dove is by its lack of a black neck collar marking.

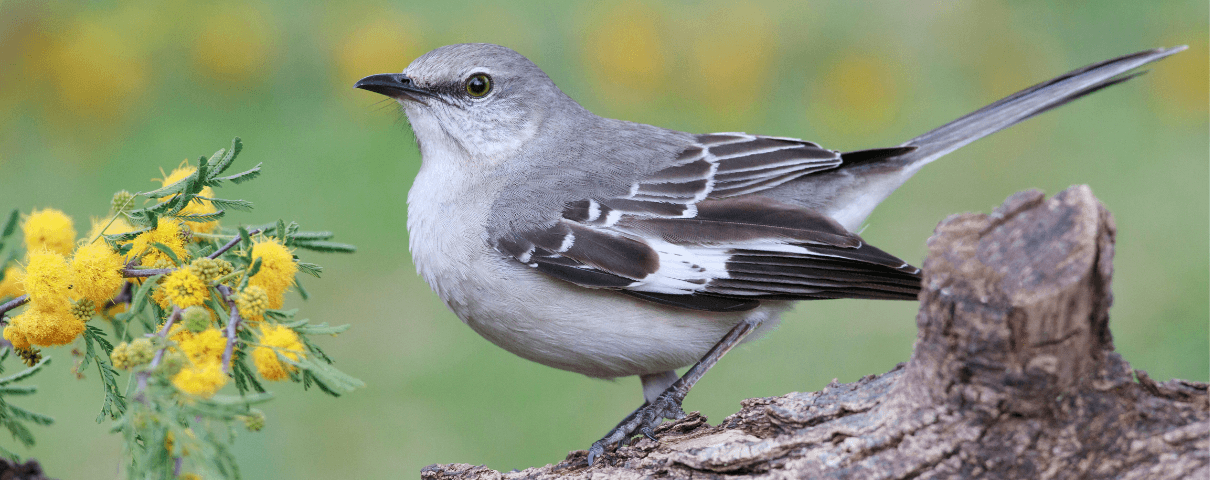

Northern Mockingbird

Mockingbirds are expert singers, continuously adding new imitations of other birds' songs to their repertoires, and sometimes mimicking unnatural sounds as well, such as the whooping of car alarms. In fact, Northern Mockingbirds may learn up to 200 different songs! Single males may even sing throughout the night (loudly), to the annoyance of people trying to get a good night's sleep. These medium-sized, long-tailed gray songbirds, which sport conspicuous white wing patches and outer tail feathers, prefer open habitats with a scattering of shrubs and small trees. They eat a wide variety of fruits, invertebrates, and even small vertebrates such as lizards.

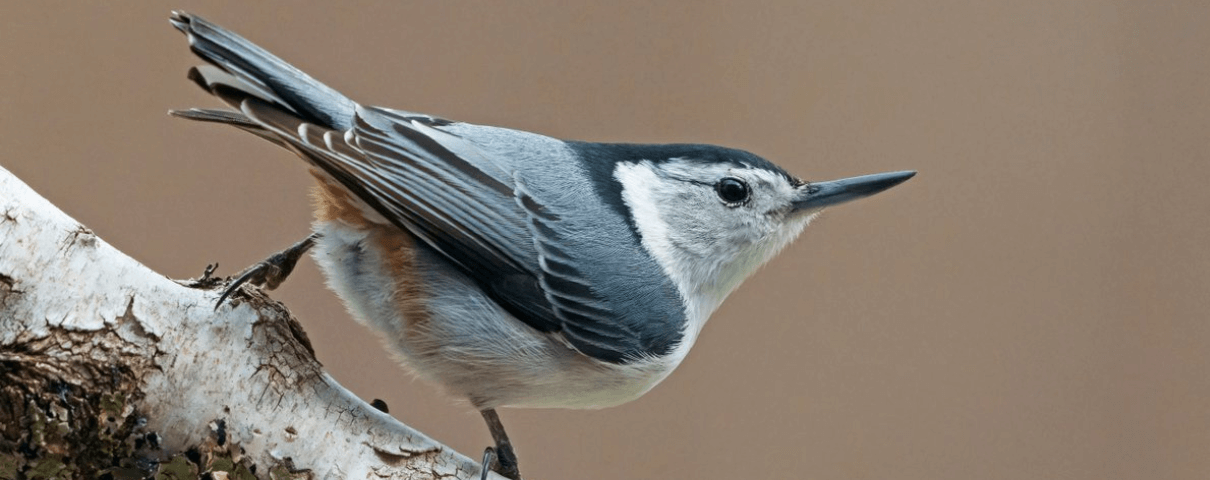

White-breasted Nuthatch

You can recognize this bird by its white face and underside, bluish back and wings, and dark crown (black in males and gray in females), its nasal “yank-yank” call, and its habit of creeping down tree trunks headfirst. Year-round residents, even in cold areas, nuthatches nest in natural cavities and old woodpecker holes. They survive the winter by caching seeds in bark crevices to eat later. Another nuthatch species, the conifer-loving Red-breasted Nuthatch, is also a common backyard visitor in much of North America, especially in winter.

American Goldfinch

The sunny yellow plumage of male American Goldfinches in spring and summer has earned these birds the nickname “wild canary,” but females and winter males are actually a duller, buffy color. Their yellow hue comes from pigments called carotenoids, and goldfinches have been the subject of a lot of research on plumage coloration. Depending on where you live in the U.S., you may have American Goldfinches in your neighborhood in summer, winter, or year-round. They eat seeds almost exclusively, primarily those of plants in the aster family, such as thistles and sunflowers.

Downy Woodpecker

Downy Woodpeckers are the smallest woodpeckers in North America. These stubby-billed, black-and-white birds live in deciduous woods and tree-filled urban and suburban parklands, where they forage on trees, shrubs, and large weeds for insects and other arthropods. Although the Downy Woodpecker and its cousin the Hairy Woodpecker look very similar, you can differentiate them based on the Hairy's larger size,longer bill, and its more strident vocalizations. Other common backyard woodpeckers in the U.S. include the Red-bellied Woodpecker (in the East) and the Northern Flicker.

Dark-eyed Junco

These unassuming gray members of the sparrow family have a surprisingly complicated taxonomic history: Until the 1970s, they were split into five different species, based on how plumage variation linked to different regions across North America. However, they were eventually “lumped” when it became clear that these groups regularly interbreed. Depending upon where you live, you may find them in your backyard in winter or year-round (as in many mountainous regions and along the entire Pacific Coast). You may see this bird's distinctive white outer tail feathers flash as it flits from one spot to another, while foraging on the ground for bugs and seeds.

House Finch

Although there are several brown finches with red faces and chests in North America, the House Finch is by far the most likely to show up at your backyard feeder. Originally only found in the West, this species was introduced to the eastern U.S. in 1939, when a few individuals were released from a pet store. House Finches became the subject of studies on infectious disease in wildlife populations when a bacterial eye infection swept through their populations in the 1990s. Like other finches, they travel in flocks and eat mostly seeds.

Song Sparrow

Song Sparrows are small, streaky brown birds that, as their name suggests, sing a cheerful, rhythmic, easy-to-recognize song. Some populations remain in one place year-round, but others migrate hundreds of miles between seasons. Although they can be found in a wide range of habitats, their favorite spots are often close to streams and other sources of fresh water.

Black-capped and Carolina Chickadees

Where their ranges overlap, these two species are a challenge to differentiate Both have black crowns and chins, white cheeks, and feisty habits. However, you can generally identify them based on their ranges (Black-capped Chickadees live in the northern half of the U.S., Carolina Chickadees in the Southeast) and songs (typically a two- or three-syllable “fee-bee” or “cheese-burger” for blackcaps, and a descending four-syllable “see-dee, see-dee” for Carolinas). Black-capped Chickadees also usually show more white on their wings, in a patch roughly the shape of a downturned hockey stick. Both species are nonmigratory, though on occasion, likely due to food scarcity, some Black-capped Chickadees wander well into the Carolina's range in late fall and winter. The two species interbreed where their ranges meet. In such areas, including parts of eastern Ohio and western Maryland, sure-fire identification may not be possible.

Backyard Birds of the Eastern U.S.

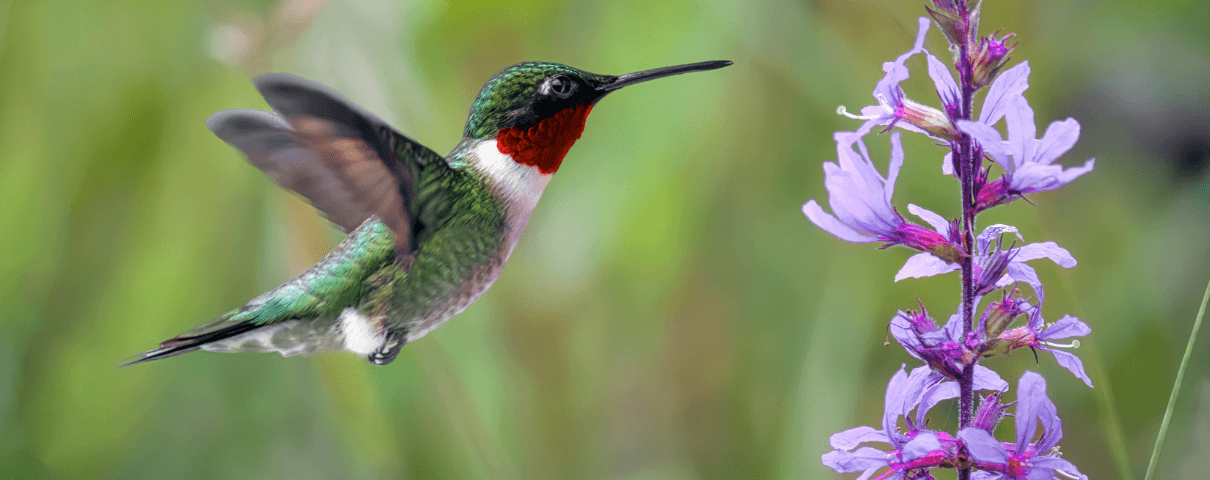

Ruby-throated Hummingbird

This is the only hummingbird that regularly breeds in the eastern U.S., so if you live east of the Mississippi and spot a hummingbird drinking from flowers or your feeder, it's likely a ruby-throat. Another giveaway: the male's metallic-looking red throat, or “gorget.” Tiny but pugnacious, males perform elaborate aerial displays to impress females, zooming through u-shaped dives and side-to-side arcs. If they can't find enough flower nectar to eat, Ruby-throated Hummingbirds have also been known to sip tree sap. They also regularly snatch tiny invertebrates, including flying insects and spiders.

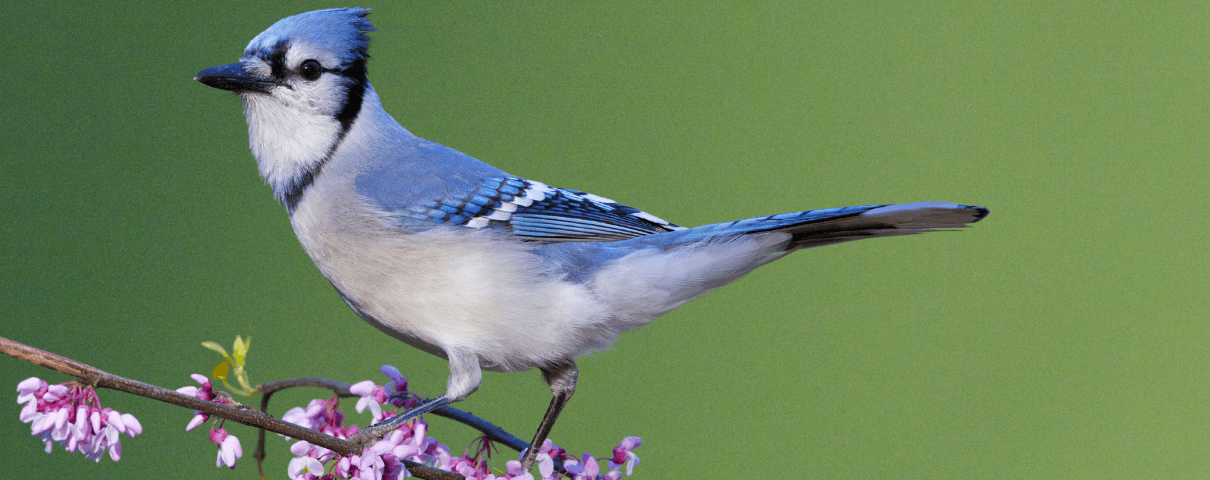

Blue Jay

The bullies of the birdfeeder, Blue Jays can be recognized by their bold blue, black, and white markings, and pointed crests. Before approaching a feeder, they often give harsh calls that sound like those of hawks, perhaps to scare off other birds that might compete for access to bird seed. Blue Jays eat a varied diet. In addition to seeds, fruit, insects, and even eggs, they particularly love acorns. Like other blue birds, Blue Jays get their color not from pigments, but from the way the structure of their feathers reflects and scatters various wavelengths of light. Although generally considered an eastern bird, the Blue Jay's breeding range extends as far west as Colorado and even Montana – where the species sometimes hybridizes with the Steller's Jay.

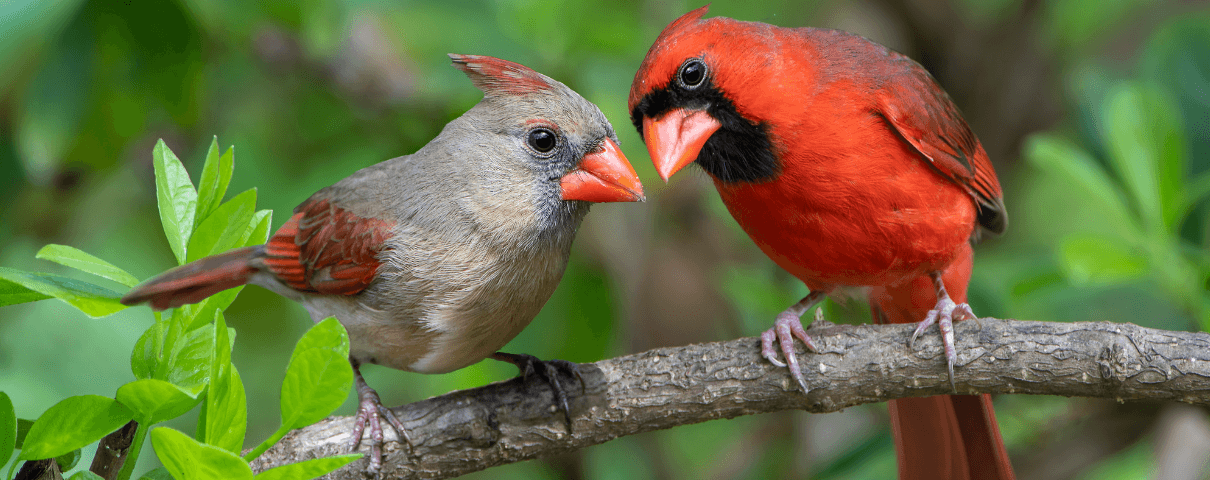

Northern Cardinal

Male Northern Cardinals are unmistakable: Look for the combination of a head crest, black mask, chunky orange bill, and brilliant red plumage. (Females are a soft grayish tan but otherwise share the same field marks.) Both males and females sing, and their ubiquitous “cheer, cheer, cheer,” and “birdie, birdie, birdie” songs can sometimes sound like car alarms. The state bird of seven states, the Northern Cardinal was originally a bird of the southern U.S., but the species has gradually expanded its range into the Northeast since at least the mid-1800s. The Northern Cardinal also occurs in the Southwest, from West Texas through southern Arizona.

Tufted Titmouse

These acrobatic little birds, which are gray with pointed crests, flit actively from branch to branch and even hang upside down as they search for seeds, insects, and spiders. They form longer-lasting family units than do many other songbirds, with young birds sometimes even hanging around for a second year to help raise younger siblings. Tufted Titmice are part of the same bird family as chickadees, and they often form mixed flocks with chickadees after breeding season. The “titmouse” name has nothing to do with rodents, but instead comes from an Old English phrase meaning “small bird.”

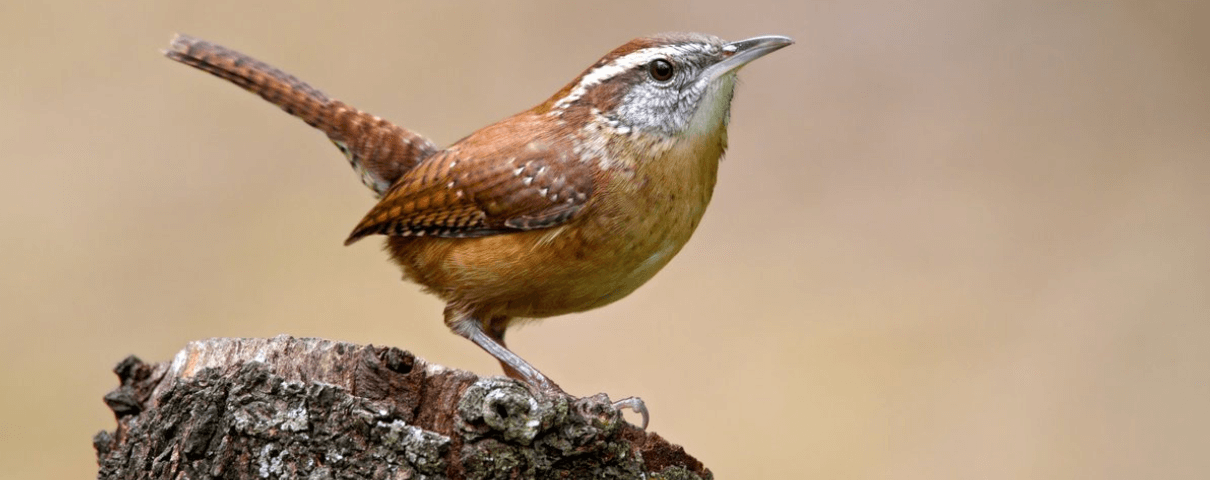

Carolina Wren

Carolina Wrens have been described as “nervous,” “shy,” and “more likely to be heard than seen,” so you might want to learn their “tea-kettle, tea-kettle, tea-kettle” song. They make a variety of other sounds as well, including a chatter. Don't be surprised to discover that the wrens are making many of the loud sounds you hear in your yard. These birds, which eat insects and spiders, forage on the ground in brushy habitat, often in pairs. They can be recognized by their rust- and cinnamon-colored plumage and white eye stripe. Other common wrens to watch out for include the Bewick's Wren in the western U.S. and the House Wren throughout most of North America.

Backyard Birds of the Western U.S.

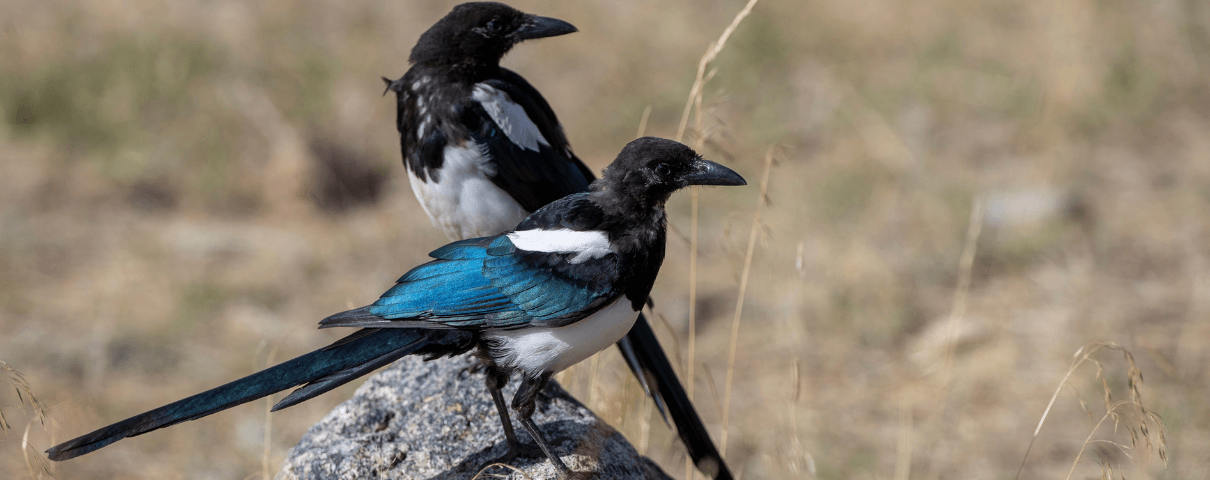

Black-billed Magpie

Magpies are striking members of the jay and crow family, boldly patterned in black and white and sporting luxuriously long tails that allow them to quickly change direction in flight. Intelligent and social, they roam neighborhoods in loose flocks, scavenging at carcasses in addition to foraging for insects and seeds. In spring, pairs work together to build large, domed nests out of sticks and mud. The related Yellow-billed Magpie is found only in central and coastal California.

Rufous Hummingbird

This species has the northernmost distribution of any hummingbird, breeding as far north as southern Alaska. (Rufous Hummingbirds that nest in Alaska make one of the longest migrations of a bird their size!) Males have a distinctive rusty (rufous) coloration, which gives the species its name. Officially listed as “Near Threatened” by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN), the Rufous Hummingbird population declined by about 67 percent between 1966 and 2019. Other common backyard hummingbirds in the western U.S. include the Anna's Hummingbird and Black-chinned Hummingbird.

Steller's Jay

Common residents of coniferous forests throughout the West, Steller's Jays can be recognized by their solid blue bodies and crested black heads. Like other members of the corvid family, they eat a broad diet of invertebrates, plant material, and sometimes even other birds. Males and females form monogamous, long-term bonds, and their raucous calls and lack of fear of humans make them easy to spot at campgrounds and in backyards. Their relatives, the scrub-jays, are also common in many parts of the West.

Spotted Towhee

Look for Spotted Towhees skulking in thickets and under shrubs, scratching at the leaf litter with both feet in search of bugs and seeds. Members of the sparrow family, they have dark heads and backs, white spots on their wings, rusty sides, and striking red eyes; their song is a simple trill. Prior to the 1990s, Spotted Towhees were considered to be members of the same species as their eastern cousin, the Eastern Towhee (once lumped under the name “Rufous-sided Towhee”).

Lesser Goldfinch

Closely related to, but a bit smaller than American Goldfinches, Lesser Goldfinches occupy similar habitats and eat similar foods, although they're somewhat more likely to eat buds and small fruits in addition to seeds. Common in the Southwest, this species is rapidly expanding north into Washington and Idaho, among other states. In shape and habits the Lesser and American Goldfinches are very similar. Unlike American Goldfinches, however, brightly colored breeding male Lesser Goldfinches have black or greenish backs, meaning that their bright yellow underparts make them only “half” canary yellow.

Tips to Observe and Identify Backyard Birds

Learning to identify backyard birds is a great way to deepen our relationship with nature. There is no “right” way to learn birds, and the tactics used by new birders vary depending on personality and learning style. Regardless of skill level, you can consider yourself a “birder” if you spend time watching birds.

Here are a few basic tips that are likely to help any beginner:

- Carefully observe the bird, its markings, habits, habitats, shape;

- In books, online, or via apps, learn to identify the top 20, or top 50, most widespread species in your area;

- Sketch out details, or write notes to remember important features of the birds you see;

- Note the season and place, then confer with resources to see if they match for your bird;

- Confer with other birders on questions and/or locations for new birds;

- Once you're getting the swing of visual identification, start learning the songs and calls of the most common species around you; and

- Be patient and don't give up! Your skills and confidence will improve as you continue birding.

In addition to careful observation, there are a number of digital tools that can provide new birders with a boost. American Bird Conservancy has a large library of bird profiles, which include many common backyard birds. The Cornell Lab of Ornithology's powerful Merlin app can help confirm bird identity based on visual and sound clues. If you're interested in more formal training, Cornell also offers a wide assortment of online classes.

Feeding Backyard Birds

For millions of Americans, watching and feeding backyard birds go hand in hand. Bird-feeding brings joy to many a human heart and, in some circumstances, can be an important source of nutrition for birds. But these rewards don't come without responsibility.

First and foremost is feeder-cleaning.

Birds, like humans, face increased exposure to sickness and disease when brought in close contact, and feeders, of course, do exactly that. The consequences can be tragic: Feeders have contributed to the spread of House Finch eye disease (mycoplasmal conjunctivitis) and trichomoniasis, a respiratory disease.

Unfortunately, the danger posed by bird diseases is growing. H5N1 avian influenza, or bird flu, continues to spread unabated, raising fears that, unlike previous outbreaks, it may be here to stay. The disease has already spread throughout much of the continental United States, infecting at least 99 wild bird species, while threatening several imperiled species.

When the disease rates climb, local and state authorities typically provide public guidance on bird-feeding. If in doubt, check with health or wildlife departments before filling your feeder.

The good news is that regular feeder cleanings can help reduce disease spread. Feeders need to be completely scrubbed with a 10 percent non-chlorinated bleach solution every few weeks to prevent the spread of disease.

In addition to cleaning, it's important to consider feeder placement. Carefully consider where the feeder is placed with relation to any reflective glass, such as windows or patio doors. (For tips, see our collisions page.) Also, placing feeders within reach of outdoor cats or other predators can spell disaster for backyard birds.

Despite these challenges, you don't need to pack away your feeder. The bottom line is that backyard-feeding is fine for birds as long as adequate consideration and proper care are taken to prioritize birds' welfare.

Feeders, however, aren't the only way to attract birds. There are a number of simple steps, like cultivating or purchasing native plants that attract hummingbirds and other birds naturally, while also improving habitat for other wildlife.

Threats to Backyard Birds

In less than a single human lifetime, 2.9 billion birds have been lost from the United States and Canada. These loses aren't restricted to rare or lesser-known birds — even familiar and backyard birds have suffered devasting declines. The Dark-eyed Junco population, for example, has declined by an incredible 175 million individuals. The White-throated Sparrow has lost 93 million.

Scientists believe these losses are likely due to a combination of threats, including non-native predators (commonly unrestrained outdoor cats), window collisions, pesticides, plastics, and climate change. However, the largest underlying threat is likely habitat loss. Large swathes of critical habitat continue to disappear throughout the Americas, making it harder for birds to survive and reproduce.

Give Backyard Birds a Hand

Helping birds bounce back requires teamwork, and we all have a role to play. Here are a few ways you can get involved:

Policies enacted by Congress and federal agencies, such as the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, have a huge impact on America's birds. You can help shape these rules for the better by telling lawmakers to prioritize birds, bird habitat, and bird-friendly measures. To get started, visit ABC's Action Center.

Don't overlook the impact you can have at home: Living a bird-friendly life can have an immediate impact on the birds around you. Doing so can be as easy as adding native plants to your garden, avoiding pesticides, and keeping cats indoors. To learn more, visit our Bird-Friendly Life page.

American Bird Conservancy and our Migratory Bird Joint Venture partners have improved conservation management on 8.5 million acres of U.S. bird habitat — an area larger than the state of Maryland — over the last ten years. This is a monumental undertaking, requiring the support of many, and you can help by making a gift today.