The gregarious Pinyon Jay, known by the folk name Blue Crow, is so closely tied to the life cycle of coniferous trees that it's even named for its favorites, the pinyon pines.

The gregarious Pinyon Jay, known by the folk name Blue Crow, is so closely tied to the life cycle of coniferous trees that it's even named for its favorites, the pinyon pines.

This crestless jay of southwestern pine and juniper forests is the only representative of its genus, Gymnorhinus, which means "bare nostrils." Unlike many of its close relatives such as the Blue Jay and Common Raven, the Pinyon Jay lacks feathers at the base of its bill to cover its nostrils. This anatomical difference means that the bird can probe sticky pine cones for seeds — a staple of its diet — without coating feathers with sap.

Flock Life

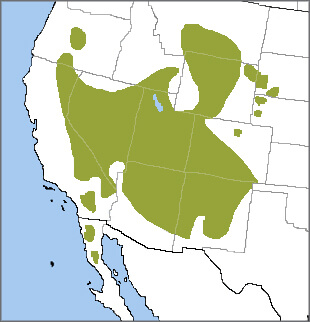

Like the Green Jay, the Pinyon Jay is nonmigratory (resident) and social. Although it follows no regular migration pattern, it does wander, occurring irregularly within a wide range, primarily in semi-arid mountains and plateaus from eastern California across Nevada and Utah, to parts of Wyoming and southeastern Idaho, much of northern Arizona and New Mexico, western Colorado, and south-central Montana. Isolated populations occur in central Oregon, western South Dakota and Nebraska, southern California, and northern Baja California, Mexico.

What turns a resident bird into a nomad? The Pinyon Jay may disperse from its core range when food is scarce; this phenomenon, known as irruption, can be observed in other bird species including the Evening Grosbeak and Pine Siskin.

Outside the breeding season, Pinyon Jays are often found in large, loose flocks numbering as many as 500 birds. The composition of each flock changes during the breeding season, when pairs form loose colonies, splitting off from large congregations.

Like other members of the Corvidae family, the Pinyon Jay has a relatively unmelodic voice, described as a rhythmic, repeated krawk-kraw-krawk:

(Pinyon Jay audio by Frank Lambert, XC362423, accessible at www.xeno-canto.org/362423)

Nuts for Jays

Pinyon Jays and pinyon pines evolved alongside each other. The jays disperse the large, wingless pine seeds over long distances and in return have access to a rich food source, as well as areas for cover and nesting. So close is this association that in years when the pine seed crop is low, the Pinyon Jay population also drops.

When pine seeds are abundant, Pinyon Jays store thousands in different caches in the ground and in tree crevices. This species has a remarkable memory and can relocate these hidden seeds months later – even under several feet of snow. The few seeds that remain below ground may germinate into young trees.

Ever social, Pinyon Jays forage through the pines in groups, filling their throats with seeds, then moving to a traditional caching area, often the same place used from year to year. Pairs have even been seen coordinating their caching so each bird knows the location of its mate's food supply.

Despite its close association with pinyon pines, the Pinyon Jay does not live on pine nuts alone. This bird is omnivorous, sometimes eating not only other nuts and fruits, but insects as well. As with other birds, nestlings are fed an insect-rich diet, which provides the protein they need to grow quickly and successfully fledge.

Flexible Nester

The Pinyon Jay is a cooperative breeder with a distinct social hierarchy, and individuals tend to remain in the same flock they were born in. This species has been recorded nesting in nearly every month of the year. Food availability appears to be the main driver: When pine seeds are abundant, the Pinyon Jay may begin to nest in February, making it one of the earliest-nesting songbirds in North America.

Pinyon Jay with nut, © Marie Read

Flocks of Pinyon Jays return to traditional breeding areas each year, nesting in loose colonies about 50 to 500 feet apart, in bulky open-cup nests. They usually raise only one clutch per year but will re-nest if initial attempts fail, and may even raise a second brood if food abundance and climate conditions allow.

Millions of Pinyon Jays Lost

A recently published report detailing the loss of more than a quarter of America's birdlife includes troubling statistics on the Pinyon Jay, which has lost about 2.3 million individuals — a 78.7-percent population decline — since 1970. The biggest threat to the species is the loss of its pinyon-juniper habitat.

ABC has responded to the news of the widespread bird declines with our 50-50-5 conservation plan, which includes a commitment to save 50 flagship bird species, protect and conserve 50 million acres, and fight five critical threats. You can help us implement this plan, or take other measures to help reverse this distressing decline. Find out more about how you can help recover the Pinyon Jay and other rapidly declining bird species here.

Donate now to help reverse widespread bird population declines!