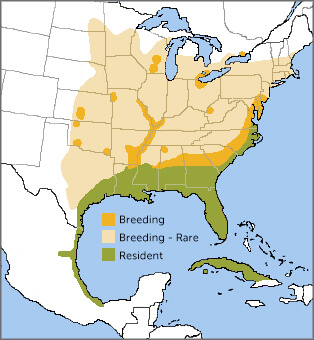

King Rail range map by Birds of the World, NatureServe.

The King Rail was first described in 1834 by the preeminent ornithologist and artist John James Audubon. This largest North American rail species is about the size of a chicken and is sometimes locally called the "Marsh Hen."

Unlike smaller nocturnal relatives, including the Black Rail, the King Rail is active during the day. Much of the bird's time is spent behind dense cover, but lucky viewers might spot one stalking along the marsh edge. While not often seen, this species is frequently heard.

Named for a Noise

Nineteenth-century farmers likened one of the King Rail's many calls to the sound of a rider or teamster clucking to horses. This "chuck-chuck" call earned the bird the name "stage driver," a true throwback to another time. A low, grating call, also described as "kek-kek-kek," is usually heard during the day, while a bird is staking out or patrolling territory or courting:

Another commonly heard call, given all year by both males and females, is a series of short grunts that often accelerates near the end:

Marsh Royalty

This species nests in freshwater and brackish wetlands along the Atlantic coastal plain, around the Mississippi River and Great Lakes, including in southern Ontario, and in scattered inland wetlands elsewhere in the East. Birds nesting in the Southeast are permanent residents, while more northerly nesters migrate, wintering in the southern United States and Mexico.

Two subspecies are recognized, one on the North American mainland and one resident in freshwater marshes of Cuba.

The King Rail is closely related to the Clapper Rail, a denizen of saline and brackish habitats. The two may interbreed where fresh- and saltwater marshes meet. Ornithologists aren't always clear on how to delineate the two skulking species' populations.

Dunking and Dining

Like other wetland birds including the Black-necked Stilt, the King Rail forages for food in shallow water and mud, usually sticking close to dense marsh cover. It's an omnivore, catching crayfish, crabs, small fish, insects, and snails, but also eats some seeds and other plant matter. When feeding on land, a King Rail will often carry a food item back to the water to dunk it before eating.

The birds regurgitate indigestible parts of their food in pellets, as do Ospreys, Belted Kingfishers, and Great Horned Owls.

King Rail chick. Photo by Nattapong Assalee/Shutterstock

Covert Flashes, Chases, and Crayfish

Males aggressively defend territory, chasing off rival males and even rails of other species. While courting, a male struts in front of a female with his tail held vertically, showing off white undertail coverts. He may also follow a female around in a "pursuit display" or offer her a crayfish or crab.

Unlike many other birds, the male takes the lead in building the nest, a platform of vegetation located in a clump of grass or sedges, usually about a foot above water or land. The nest features a canopy woven over the top and a ramp leading down from the entrance.

Both parents take turns incubating the clutch of eight to 11 eggs. A few hours after hatching, the downy black young leave the nest. They are then attended by both parents, which feed them during their first few weeks of life. The chicks learn how to gather food by observing their parents and can forage on their own at four to six weeks old. In the southern part of their range, King Rails may raise two broods per year.

Like ducks, such as the American Black Duck, King Rails molt completely after nesting, becoming flightless for almost a month. During that vulnerable time, they become even more elusive, hiding deep within the marsh vegetation.

Waning with Wetlands

Habitat loss is the greatest threat to this species. Over the past 50 years, the population has dropped 86 percent due to the filling and draining of wetlands for industrial, agricultural, and urban development. Another threat is posed by pesticides leaching into the birds' habitats.

ABC considers the King Rail to be among the top five bird species in decline, drawing this conclusion from data in a 2019 Science study that noted the loss of 3 billion birds in the U.S. and Canada since the 1970s.

Much of King Rails' remaining wetland habitat falls within national wildlife refuges and other protected areas. Protection and restoration of remaining wetlands are critical for the long-term survival of the species.