The robin-like ʻOmaʻo, also known as the Hawaiian Thrush, is one of only two endemic thrushes left in Hawaii. (The other species, the Puaiohi, is found on Kaua‘i.) Once there were endemic thrushes on each of the main Hawaiian Islands, but these three species are now extinct, victims of the habitat destruction and introduced predators and diseases that have decimated so many other Hawaiian birds.

The robin-like ʻOmaʻo, also known as the Hawaiian Thrush, is one of only two endemic thrushes left in Hawaii. (The other species, the Puaiohi, is found on Kaua‘i.) Once there were endemic thrushes on each of the main Hawaiian Islands, but these three species are now extinct, victims of the habitat destruction and introduced predators and diseases that have decimated so many other Hawaiian birds.

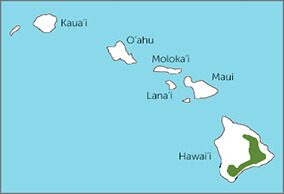

These unassuming brown-and-gray birds once ranged over most of the Big Island but are now found mostly in high-elevation native rainforest on the eastern slopes of the Mauna Kea and Mauna Loa volcanoes. Other native birds found in the same habitat include ‘Apapane, ‘I‘iwi, and Hawai‘i ‘Amakihi.

ʻOmaʻo tend to perch quietly in the forest canopy or midstory, where their unobtrusive coloring makes them hard to spot. They have a characteristic habit of fluttering their wings while perched, which may give their location away to an attentive observer.

Last Native Fruit-eater

Like other thrushes such as Wood Thrush and Swainson's Thrush, ʻOmaʻo are primarily fruit-eaters, feeding on a wide variety of fruits and berries of native shrubs and trees. They also forage for snails, spiders and insects throughout the forest canopy and on the forest floor.

As Hawai‘i Island's last native fruit-eating bird in the wild, this thrush plays an important role in re-establishing native understory plants such as ‘olapa, ‘ohelo, and akala, spreading seeds after they pass through the bird's digestive tract.

Sign up for ABC's eNews to learn how you can help protect birds

Solitary Singer

Due to their inconspicuous appearance, ʻOmaʻo are often first detected by voice. Their loud, distinctive songs and calls are given by both sexes.

Males also perform a flight-song display known as “skylarking" during courtship.

ʻOmaʻo are solitary birds that don't join mixed flocks. They can be found in pairs throughout the year and have strong pair bonds lasting at least one breeding season. Juvenile birds, unlike adults, have distinctive scalloped plumage. They may remain in the area where they hatched for up to six months.

‘Oma‘o by Hayataro Sakitsu

Found Only on the Big Island

Although it is one of the more common Hawaiian endemic birds, the entire ʻOmaʻo population exists only on the Big Island in scattered populations. The species has suffered a significant range contraction and is found in less than 30 percent of its former range, so is considered vulnerable.

Encouragingly, the persistence of some small populations of ‘Oma‘o at lower elevations could indicate that some have developed resistance to mosquito-borne diseases such as avian malaria – a disease that threatens many of the remaining Hawaiian forest bird species.

Saving Hawaiian Birds and Their Habitats

When it comes to Hawai'i, our top priority is to prevent extinctions of native Hawaiian birds. One of our priority species, the Palila, once ranged across Hawai'i but now numbers only about 2,000 birds found in less than five percent of their historic range. Working with the State of Hawai'i and the Mauna Kea Forest Restoration Project, we are restoring native forests in important areas for Palila, removing invasive predators, and maintaining the fence that protects the remaining forest from browsing non-native sheep and goats.

Home is Where the Habitat Is

Whether birds are nesting, feeding, migrating, or wintering, healthy habitat is the key. But habitat loss and degradation are the main drivers of bird population declines. Meanwhile, threats such as collisions with glass and wind turbines, deadly pesticides, and free-roaming cats compound the impacts of habitat degradation.

Donate to support ABC's conservation mission!