About

The elegant American Avocet is a striking sight at any time of the year. This gregarious shorebird is a close relative of another eye-catching bird, the Black-necked Stilt. Both species have long necks and legs and flashy black-and-white plumage. However, the head, neck, and upper chest of the American Avocet are whitish and then turn a rich rusty-peach color during breeding season. The avocet's long, pastel-blue legs (very different from the stilt's bright-pink striders) earned it the folk name "blue shanks."

The Scoop on Avocet Bills

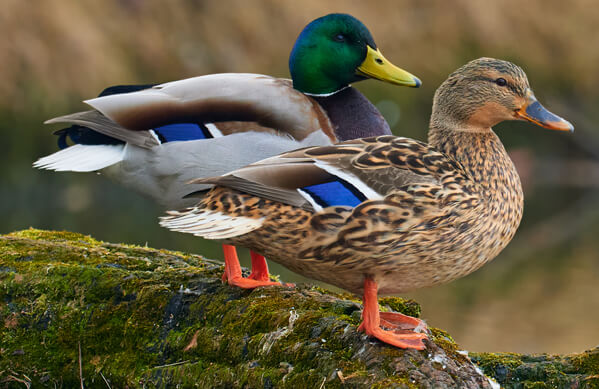

The American Avocet belongs to a genus of shorebirds named Recurvirostra, from the Latin word recurves (curved backwards) and rostrum (bill). True to this name, the American Avocet's long, thin, black bill turns up at its tip. The curvature differs by gender: While the male's bill is slightly longer, the female's is more upturned. This is a handy gender identification tip for a species in which the sexes otherwise look the same.

Songs and Sounds

The American Avocet is particularly vocal at its nesting colonies. Its loud calls include a shrill “wheet” and a repeated “kleek.” Listen here:

Calls:

Pairs calling:

Breeding and Feeding

American Avocets are monogamous during the breeding season, and pairs nest in loose colonies. Males and females perform elaborate displays to establish and maintain pair bonds, including crouching, bowing, and swaying side to side. A male and female will defend their territory from other avocets in an interesting “circle display,” in which the pair and intruding birds stand bill-to-bill in a circle, while calling and dipping their bills down toward the water.

Once mated, the female American Avocet scratches out a simple scrape for a nest, sometimes lining it with dry grass or mud. Nests are built on a sandy shore or mud flat. If rising water threatens the nest, the avocet pair quickly adds materials such as sticks, feathers, and vegetation to raise the nest and eggs above water level.

The female lays an average of four eggs, which her mate joins her in incubating for close to a month. The pair aggressively defends their nest and young with alarm calls and distraction displays, and will also dive-bomb intruders that venture too close.

Both parents tend the chicks, which can walk, swim, and even dive just a day after hatching. A month after leaving the nest scrape, young avocets are able to fly. The American Avocet raises one brood per season.

Stirring Up Supper

The American Avocet is most often seen foraging in shallow waters, such as pools dotting extensive tidal mud flats or the edges of lakes. It hunts both day and night, swinging its long bill from side to side through the water in a scythe-like motion that stirs up prey. Although it mainly feeds on aquatic insects and small crustaceans (particularly brine flies and shrimp), it may also consume some seeds. Although mostly a wader, this shorebird can swim and also may “dabble” in the manner of a Mallard or American Black Duck when feeding in deeper water, tipping its hind end up while submerging its head to seek food items. Social diners, American Avocets often feed in large flocks of 100 or more birds.

Region and Range

The American Avocet breeds in both fresh and salt water habitats throughout western North America, often using ephemeral wetlands in otherwise arid regions. After breeding, this species gathers in large migratory flocks that follow a wide path south through many U.S. states. Unlike long-distance shorebird migrants such as the Red Knot, the American Avocet does not travel very far, wintering along the California and Gulf coasts, south through Mexico. Small numbers winter in some coastal areas of Central America.

Conservation

The loss of wetlands due to development and climate change is the biggest threat facing the American Avocet. Another danger is posed by pesticides leaching into wetlands. Harmful chemicals can accumulate in feeding birds and may affect nesting success.

Help support ABC's conservation mission!

ABC is working with partners to protect and restore wetlands in parts of North America, including where few remain. Read about one such project in West Texas here. We also advocate for the North American Wetland Conservation Act, which provides grants to fund this work.

Get Involved

Policies enacted by the U.S. Congress and federal agencies, such as the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, have a huge impact on migratory birds. You can help shape these rules for the better by urging lawmakers to prioritize birds, bird habitat, and bird-friendly measures. To get started, visit ABC's Action Center.

Living a bird-friendly life can have an immediate impact on migratory birds in the United States. Doing so can be as easy as adding native plants to your garden, avoiding pesticides, and keeping cats indoors. To learn more, visit our Bird-Friendly Life page.

American Bird Conservancy and our Migratory Bird Joint Venture partners have improved conservation management on more than 8.5 million acres of U.S. bird habitat — an area larger than the state of Maryland — over the last ten years. That's not all: With the help of international partners, we've established a network of more than 100 areas of priority bird habitat across the Americas, helping to ensure that birds' needs are met during all stages of their lifecycles. These are monumental undertakings, requiring the support of many, and you can help by making a gift today.