About

The small, sand-colored Piping Plover is named for its melodic, plaintive whistle. It's a beautifully camouflaged shorebird of beaches and barrier islands — habitats also favored by species such as the Snowy Plover and Least Tern. A breeding-season adult can be identified by its black-tipped orange bill, yellow-orange legs, black brow band, and incomplete black neck ring (less pronounced in females).

Piping Plovers are dependent on safe, clean beaches to thrive, but these same places are popular with people. Protective measures to help increase populations of this species, such as fencing off nesting areas and limiting beach access, are essential for this bird's continued survival.

Plovers are known for their “foot trembling” dance: Dashing along the beach, the bird suddenly stops and extends one foot to rapidly pat the sand. The resulting vibrations are thought to bring worms and other prey to the surface. Foot-tapping may also startle insects into moving, making them easier to catch.

Songs and Sounds

The Piping Plover's calls include a clear, plaintive-sounding whistle: “peep” or "peep-lo," a series of descending whistles given during courtship displays, and a low series of “pehp, pehp, pehp” alarm calls.

Listen to a Piping Plover's whistles:

Patrick Turgeon, XC328023. Accessible at www.xeno-canto.org/328023.

Hear a few Piping Plover calls:

Will Sweet, XC494406. Accessible at www.xeno-canto.org/494406.

Breeding and Feeding

Beach Sprites

The male Piping Plover, newly arrived from the wintering grounds, first stakes out a territory, then begins displaying to attract a mate. In one aerial display, a male will fly in figure-eight patterns while constantly chirping to a female. On the ground, he approaches her in an upright posture with a high-stepping gait.

The male will also create several "starter" nest scrapes in the sand to attract a female, who will finish one after she accepts a mate. The female then lines the scrape with shells and pebbles, perfectly camouflaging it. Once mated, the female lays her clutch, which averages four eggs. Both male and female take turns brooding the eggs for about one month.

Piping Plover chicks hatch able to walk, run, and feed by themselves within hours of hatching. Like many other plover species such as the Killdeer, the Piping Plover employs a “broken wing display" when threatened to lead potential predators away from its chicks and nest.

This species usually raises just one brood per season, although a female will renest if her first clutch is destroyed. After her eggs hatch, the female often leaves the breeding area, leaving the male to raise the chicks alone.

Piping Plovers resemble wind-up toys as they forage along the beach in abrupt dashes and pauses. They feed on a wide variety of insects, marine worms, and crustaceans, picking their prey from above or just below the sand or ocean wrack with short, rather stubby, bills.

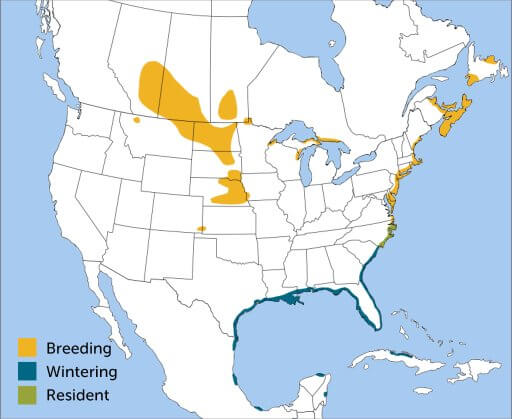

Region and Range

There are two recognized subspecies of Piping Plover, divided into three separate geographic populations in the United States and Canada. These populations are found in the Northern Great Plains; along the shores of the Great Lakes; and on the Atlantic coast. Birds from all three groups migrate south to winter on the southern Atlantic and Gulf coasts of the United States, as well as in the Bahamas and Cuba.

For several years, ABC's former employee Kristen Vale monitored a bird from the Endangered Great Lakes population. Read about her experience with Monty — of the celebrity Piping Plover pair Monty and Rose — here!

While Piping Plovers have increased in number in recent years, the species is still listed under the Endangered Species Act. It is considered Endangered in the Great Lakes region and Threatened in the remainder of its U.S. breeding range. The species is also listed as Endangered in Canada.

Conservation

Plight of a Plover

Piping Plover populations have seen significant increases since protection programs began, but challenges continue. One example: Nesting Piping Plovers at Jones Beach, near New York City, were threatened by a colony of free-roaming cats, which included abandoned pets. ABC and partners intervened, noting the need to uphold protections for this federally protected species, and the cats were relocated to sanctuaries — a win for birds that also improved the beach for people.

Habitat loss has caused serious declines and threats to Piping Plover populations, particularly from shoreline development and stabilization projects, energy development, climate change, and plastic pollution. Predation from free-roaming cats, off-leash dogs, and wild animals is also a significant threat. Like other beach-nesting birds, Piping Plovers are vulnerable to off-road vehicles, which tear up habitat and crush eggs and chicks.

Help support ABC's conservation mission!

ABC's Gulf Coastal program is working with many different partners across the Gulf Coast states to help bring back populations of beach-nesting birds. In Texas, we focus on the protection and monitoring of migrating and wintering Piping Plovers, as well as nesting species such as the Black Skimmer and Wilson's Plover. These efforts include signage on beaches and public education and outreach programs.

In addition, ABC and partners launched SPLASh (Stopping Plastics and Litter Along Shorelines), a program to reduce pollution along the Texas coast — known as the country's most littered coastline. SPLASh conducts community cleanups, collects data on litter, and inspires action through awareness raising and education.

Get Involved

Policies enacted by the U.S. Congress and federal agencies, such as the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, have a huge impact on migratory birds. You can help shape these rules for the better by telling lawmakers to prioritize birds, bird habitat, and bird-friendly measures. To get started, visit ABC's Action Center.

Living a bird-friendly life can have an immediate impact on migratory birds in the United States. Doing so can be as easy as adding native plants to your garden, avoiding pesticides, and keeping cats indoors. To learn more, visit our Bird-Friendly Life page.

American Bird Conservancy and our Migratory Bird Joint Venture partners have improved conservation management on more than 8.5 million acres of U.S. bird habitat — an area larger than the state of Maryland — over the last ten years. That's not all: With the help of international partners, we've established a network of more than 100 areas of priority bird habitat across the Americas, helping to ensure that birds' needs are met during all stages of their life cycles. These are monumental undertakings, requiring the support of many, and you can help by making a gift today.