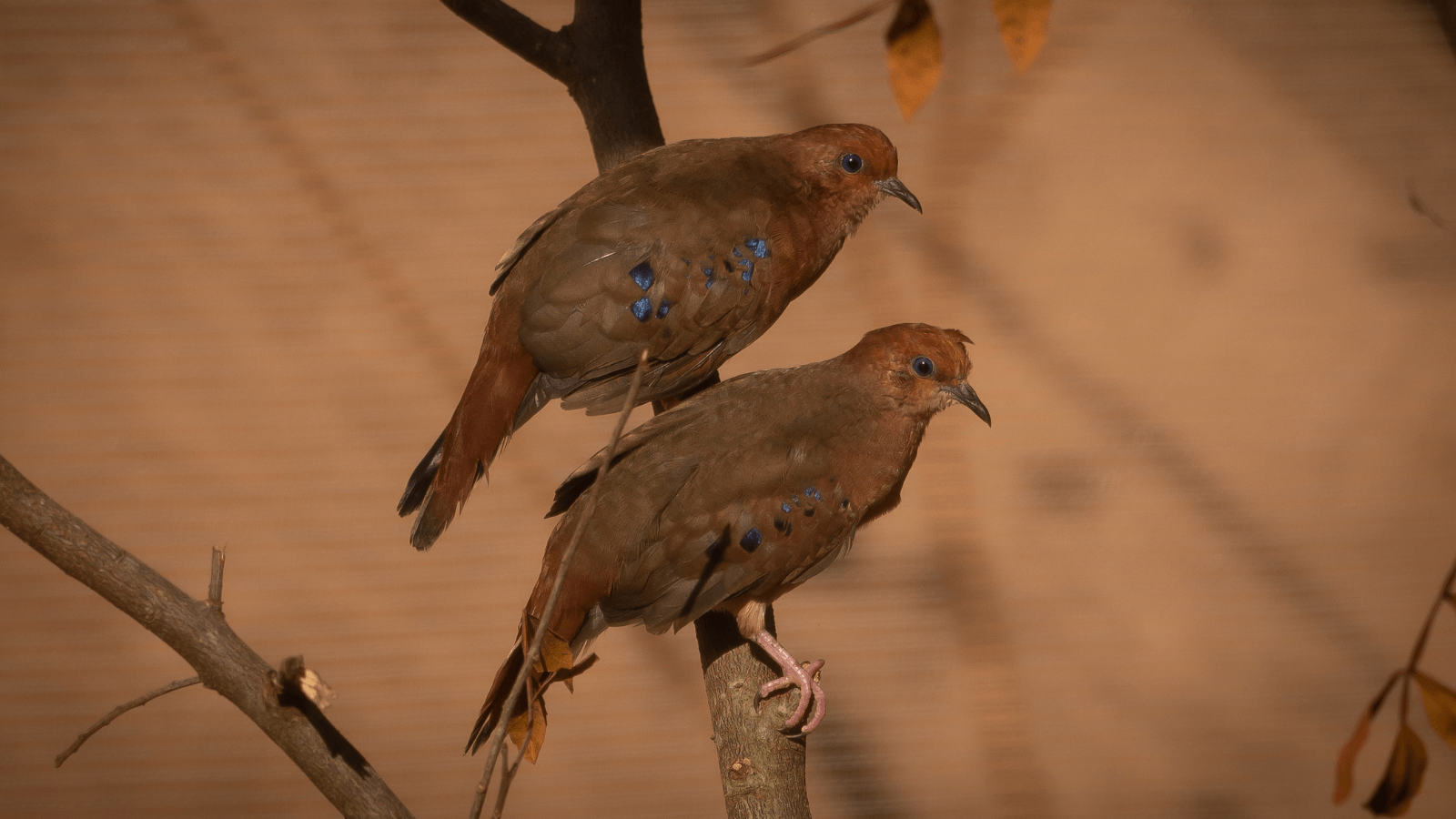

Critically Endangered Blue-eyed Ground-Dove Chicks Reared in Captivity for First Time

Conservationists in Brazil have successfully hand-raised two Blue-eyed Ground-Doves in captivity, a heartening milestone for one of the most Critically Endangered birds in the world. The two chicks represent about 12 percent of the total population of this species, and at least two individuals safe from predators and other threats.

“This achievement buys us more time to understand the species' needs and implement protections in the wild that would be better for it in the future," said Bennett Hennessey, Brazil Program Coordinator for American Bird Conservancy (ABC).

This small dove with russet feathers and striking blue eyes was considered a lost species for much of the 20th century until its rediscovery in 2015. But initial joy at finding the species morphed into concern when biologists discovered there were just 16 individuals left in the wild, in a tiny area of the Brazilian state of Minas Gerais. Now conservationists are launching a new plan to help bolster this tiny wild population, rearing some chicks in captivity to provide an insurance population for the species.

Rediscovered in the Nick of Time

When ornithologist Rafael Bessa rediscovered Blue-eyed Ground-Doves in 2015, the species hadn't been seen for 75 years. It soon became clear why — the last remaining population of this shy bird was down to its final handful of individuals living in a relatively small area far to the east of the doves' known range.

After the discovery, conservationists sprang into action to protect habitat in the bird's range and minimize future threats. In 2018, Brazilian conservation organization SAVE Brazil established a 1,465-acre Blue-eyed Ground-Dove Reserve covering much of the species' range; the rest fell under the protection of a new state park. ABC supported the reserve and subsequent management and monitoring through a grant from the Latin American Reserve Stewardship Initiative (LARSI), a program of ABC and March Conservation Fund.

Nests are now monitored each year in the protected area, but the dove's numbers have not gone up. Very few chicks make it to adulthood each year. Predators often eat eggs and chicks before they can fledge, and scientists worry that remaining adults might also be laying fewer eggs due to a lack of genetic diversity.

In 2019, an international group of scientists came together at bird sanctuary Parque das Aves for a meeting facilitated by the IUCN's Conservation Planning Specialist Group to assess the situation and decided it was time to try raising some birds in captivity to keep the species from slipping through their fingers. The meeting launched a multi-year effort to make that vision into a reality.

“It all seemed so abstract in that first meeting in 2019 — it really was just a dream,” said Carmel Croukamp, CEO of Parque das Aves. “To get where we are now required a series of steps, each one very complex, so we never really dared to imagine that we would get there.”

The Pigeon Milk Problem

Conservation biologist Joe Wood first learned about the Blue-eyed Ground-Dove's plight at that 2019 meeting. Wood, now the Manager of International Conservation Programs for the Toledo Zoo, is one of the world experts on hand-rearing pigeons, and he was brought in to help consult on the process.

Meeting participants decided that bringing adult birds into captivity to breed was just too risky, he said. They decided that their best bet was to monitor nests during the breeding season and have trained professionals carefully move some eggs from the nests to hatch in captivity. That way, the pair in the wild would consider that attempt a failure and be encouraged to make a second nesting attempt, while the eggs brought into captivity would gain safety from predators and a better chance of making it to adulthood. This would spare any adult birds the stressful adjustment of being collected themselves and taken into a new environment to breed.

There was just one problem — hand-rearing doves and their relatives is notoriously difficult due to a quirk of this group's parenting technique. “Pigeons and doves are weird,” Wood said. “They produce a substance called crop milk, which is a secretion from the lining of the crop produced by both parents. It's quite similar to the milk produced by mammals.”

Newly hatched chicks only rely on crop milk for their first couple of days of life, but until very recently, Wood said, no captive rearing attempt succeeded in getting pigeon and dove chicks past those first crucial days. In more recent years, the Toledo Zoo and other organizations have managed to develop an artificial crop milk — essentially, a pigeon baby formula — to solve this problem. Wood has perfected a technique of delivering the artificial milk to hatchlings through a modified pipette, keeping them alive until they can start eating more solid food.

Parque das Aves spent time practicing Wood's technique on the more common Ruddy Ground-Dove before deciding this year that it was ready to attempt hand-rearing Blue-eyed Ground-Doves themselves. While there were still risks involved and no guarantee it would work, the bird's situation wasn't improving, and they needed to act.

The Moment of Truth

When this year's breeding season began, ornithologists monitored the nests until they identified two with eggs, which SAVE Brazil and Parque das Aves brought into a facility near the habitat. Wood was flown in to supervise the first batch of chicks, and he didn't have to wait long before it was time to jump into action.

The first chick began hatching the second day he was there, with the second close behind. Both chicks were exactly 2.14 grams — just more than the weight of two paper clips. “Just a bit bigger than your thumbnail,” Wood said. “Absolutely tiny.”

The first few days were tense. At one point, one of the chick's crops (the pouch birds use to store food before digesting it) stopped emptying, which can be a death sentence for young birds if the food begins to ferment. Wood spent hours gently stroking the little bird's neck until it resumed functioning as normal. By the time he left two weeks later, both chicks were past the most dangerous phase of development and continued to grow under the watchful eye of Parque das Aves staff.

“As the chicks matured at Parque das Aves we saw their eyes turn blue and those beautiful blue mirrored patches develop on their wings,” Croukamp said. “We saw in front of us birds we had only seen from rare photos in the wild. And they were just a few meters from the room where we all sat years back and came up with the plan.”

The two Blue-eyed Ground-Doves, now fully grown, have adapted well to their lives in an aviary built especially for them at Parque das Aves. The plan next year is to follow the same protocol again, but to try to take even more eggs into captivity. This year's success is a heartening sign that there might be hope for the species yet, and biologists will not simply have to watch as they blink out in the wild.

“It's certainly one of the most meaningful things I've done in my career,” Wood said. “I was trying not to think about it at the time, but 12 percent of an entire species is quite a thing to hold in two hands. I'm glad it worked.”

###

American Bird Conservancy is a nonprofit organization dedicated to conserving wild birds and their habitats throughout the Americas. With an emphasis on achieving results and working in partnership, we take on the greatest problems facing birds today, innovating and building on rapid advancements in science to halt extinctions, protect habitats, eliminate threats, and build capacity for bird conservation. Find us on abcbirds.org, Facebook, Instagram, and Twitter (@ABCbirds).

Media Contact

Jordan Rutter

Director of Communications

media@abcbirds.org