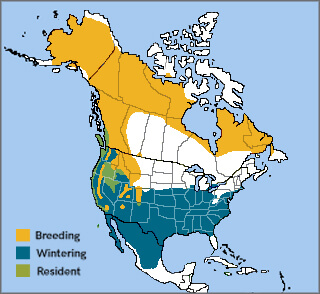

White-crowned Sparrow range map by American Bird Conservancy

The dapper White-crowned Sparrow is easily recognized by its boldly striped head, colorful pink or yellow bill, and unmarked gray breast. Like its close relative the White-throated Sparrow, this handsome bird is a widespread winter visitor in many parts of the United States, reaching well into Mexico as well.

Because of its wide distribution, geographic variation, and adaptability, the White-crowned Sparrow has been a popular study subject among North American scientists. Luis Baptista, an expert in bioacoustics, even referred to this species as "the white rat of ornithology."

A Star Subject

Decades of White-crowned Sparrow research have contributed important data that help us better understand birds, including their song development, geographic variation, physiology, breeding, and population biology.

In spring 2020, researchers in San Francisco discovered that White-crowned Sparrows quickly modified the volume and quality of their songs in response to the quieter conditions resulting from pandemic lockdowns. The ease with which the sparrows adapted to the changed soundscape suggests that more permanent reductions in urban traffic, and thus street sound volume, could lead to other beneficial outcomes for urban and suburban birds, including higher species diversity.

A 2019 study showed that ingestion of neonicotinoid (neonic) pesticides caused White-crowned Sparrows to stop eating, lose weight, and delay their southward migrations — providing proof that these widely used insecticides not only reduce birds' food supply but also directly harm them.

Researchers have also discovered that young White-crowned Sparrows sing in regional dialects, learned in the areas where they hatch and return each year for nesting. Male White-crowned Sparrows can become "bilingual" — that is, they learn neighboring birds' dialects as well as their own, and sing both.

The basic White-crowned Sparrow song begins with a clear whistle and is followed by trills and buzzes. See if you can hear regional differences between White-crowned Sparrow songs.

Listen here:

(Audio: Subspecies pugetensis by Richard Hoyer, XC253833. Accessible at www.xeno-canto.org/253833. Subspecies leucophrys by Guy Breton, XC478421. Accessible at www.xeno-canto.org/478421. Subspecies nuttalli by Ryan Winkleman, XC321716. Accessible at www.xeno-canto.org/321716. Subspecies gambelii by Logan McLeod, XC432599. Accessible at www.xeno-canto.org/432599)

Wide-ranging White-crowned

This familiar songbird breeds from Alaska and Manitoba east to Labrador and Newfoundland, and south into the western mountains to northern New Mexico and central California. It is also found year-round from southwestern British Columbia south along the Pacific Coast to Santa Barbara County, California. The species also has an extensive winter range, from southern British Columbia, Idaho, and Nebraska east to the Atlantic, and extending as far south as central Mexico.

The White-crowned Sparrow is a backyard and even urban bird in parts of the West. In much of the East, however, it is widespread but less common, often associated with more rural habitats on its wintering grounds.

There are four recognized White-crowned Sparrow subspecies, which vary subtly in appearance and behavior. Their bill color varies from light yellow to pink, and the color of their lores (the feathers between the bill and the eye) can be white, black, or gray. These subspecies also vary greatly in the patterns and timing of their migration. The most migratory group travels over 2,600 miles, from Alaska to as far south as Mexico each fall, then back again each spring. In contrast, one western subspecies is sedentary (nonmigratory).

Particularly in the West, birders can find the subspecies identification game challenging but rewarding: Three subspecies nest in different parts of California, for example, often mingling during migration and in winter.

Immature White-crowned Sparrow showing a more muted pattern of stripes on the head. Photo © Michael Stubblefield

Flexible Foraging

Like others in its family, including Song, Swamp, and Grasshopper Sparrows, the White-crowned Sparrow varies its diet according to the season. In the winter, it eats grass and weed seeds, buds, and fruits, as well as sunflower and other seeds below bird feeders. During the breeding season, the Whitecrown adds insects and other arthropods to the menu.

This bird forages in different ways, scratching through leaf litter for seeds like a Spotted Towhee or even hawking insects from a low perch, an unusual feeding strategy for a sparrow.

During the winter, White-crowned Sparrows often forage in small flocks. Birders can spy them in open areas close to brushy habitat or perched on low branches within shrubby hedgerows.

Nest Runner

Male White-crowned Sparrows arrive on breeding grounds before females and quickly start singing and establishing territories. Once mated, a female builds her cup-shaped nest in a shallow depression on the ground or a few feet up in a shrub, depending on the subspecies. The nest is made of grasses, twigs, bark strips, rootlets, and other vegetation, then lined with soft materials such as feathers and animal hair. The female does all the nest-building and incubation of her clutch of two to six eggs, then broods the hatchlings until they fledge. The male pitches in after the young hatch by bringing food to the nest.

Like other ground-nesting birds such as the Henslow's Sparrow and Sprague's Pipit, the White-crowned Sparrow returns to its nest as inconspicuously as possible to conceal its location from potential predators. Typically, it lands near its nest, then creeps the rest of the way on foot. If disturbed while incubating, the female performs a distraction display by wagging her tail feathers as she runs away from the nest.

Northern subspecies of the White-crowned Sparrow usually raise only one brood, but those in the southern part of this sparrow's range may raise two, three, or sometimes four broods in a season.

First-year White-crowned Sparrows can be distinguished from adults by their more muted, though still distinctive, reddish-brown-striped head pattern. As an immature bird molts into adult plumage, the striking black-and-white head pattern appears, in time for the bird's first breeding season.

Worth Watching

Although White-crowned Sparrows remain numerous and widespread, their populations declined by about 29 percent between 1966 and 2012, according to the North American Breeding Bird Survey.

An estimated 67 percent of White-crowned Sparrows breed in and around the boreal forests of the northern U.S. and Canada. This habitat, home to numerous other breeding birds such as the Swainson's Thrush and Olive-sided Flycatcher, is known as "North America's Bird Nursery," but it faces ongoing threats from oil and gas exploration, poorly managed logging, mining, and climate change.

ABC's BirdScapes approach to conservation — which stresses the protection of nesting and wintering habitats as well as migration stopover sites — benefits the White-crowned Sparrow and many other short- and long-distance migratory species. Our advocacy programs, including Cats Indoors and Bird-Smart Wind Energy, work to reduce or remove some of the obstacles these sparrows face.

Donate to support ABC's conservation mission; 1:1 match through Dec. 31!